Blender 2.8 Facial motion capture tutorial

In this blender 2.8 tutorial by CGMatter we go over how we can use blender as a free facial motion capture solution. Track facial performance using just tracking markers and blender!

Kategori: Engelska

Motion tracking med Blender 2.8

In this blender 2.8 tutorial, by CGMatter (https://www.cgmatter.com), we go over the fundamentals of motion tracking inside blender. Specifically we go over image sequence conversion and the motion models (location, rotation, scale, affine, perspective) used for tracking.

This is the first part of a 3 part tutorial series covering everything to do with motion tracking.

TIMESTAMPS: 00:00:00 – Introduction

00:01:18 – What is motion tracking?

00:01:55 -Image sequences (theory + conversion)

00:08:33 – Switching to movie clip editor

00:10:05 – Setting up

00:11:46 – Location tracking (and some basics)

00:16:43 – Tracking panel (track speed, frames limit, etc)

00:19:16 – Search area and pattern area (optimization)

00:22:20 – Default settings vs local settings

00:23:03 – Modifying the pattern area

00:24:33 – Graphs (how to interpret X and Y data)

00:26:10 – Link empty to track

00:27:33 – Basic 3d integration

00:28:37 – Location rotation motion model (+ comparing to location model)

00:33:10 – What a tracker really stores

00:33:58 – 2 point tracking (for rotation/scaling data)

00:39:20 – Normalize

00:42:16 – Location rotation scale motion model

00:46:17 – Previous frame vs keyframe (match mode)

00:48:47 – Correlation (with a small mistake :D)

00:53:03 – Affine motion model

01:00:19 – Perspective motion model

01:13:03 – RGB color channels

01:15:10 – Closing thoughts + sneak-peek

Blender 2.8 Motion tracking #2: Even more to go over (tutorial)

In this blender 2.8 tutorial we continue developing the theory of motion tracking by going over techniques like join tracks and offset tracking. We also talk about applications like masking, plane tracks, stabilization, and compositing. TIMESTAMPS:

00:00:00 – Introduction (what we’ll go over)

00:01:11 – Setup 00:02:35 – Obstructions (join tracks)

00:08:23 – Offset tracking

00:14:52 – Stabilization (lot’s of stuff in here) – multiple trackers – stab weight – rotation/scale

00:23:21 – Color coding

00:24:36 – More stabilization – autoscale – anchor frame

00:26:51 – Compositing (stabilize 2d node)

00:32:32 – Rendering stabilized result

00:35:23 – Plane track

00:42:30 – Compositing (plane track deform node) – masking – dilate/erode node

00:49:44 – Manual hook approach

00:57:12 – Masking

01:00:16 – Mask node (compositing)

01:01:37 – Overview + sneak-peek

Blender 2.8 Motion tracking #3: Camera tracking in depth (tutorial)

In this blender 2.8 tutorial we finally go over camera tracking and the theory involved in reducing your solve error. We also talk about orientation and compositing which lets us put 3d objects in our scene.

Blender 2.8 Motion tracking #4: Camera tracking examples (tutorial)

In this blender 2.8 tutorial we review what we’ve learned about camera tracking. Specifically we try to get a good camera solve on two new shots one of which is a tripod shot.

Plaståtervinning eller växande skräphögar?

Dokumentärfilmen är uppdelad i 3 delar.

Vad vet du om plaståtervinningen i världen?

Visste du att nästan ingenting av allt vi skickar till materialåtervinning i verkligheten återvinns?

Både konsumenter och myndigheter har förts bakom ljuset med bedrägliga och illegala metoder i ett smutsigt system av gigantiska proportioner.

Vissa länder har i decennier utnyttjats som dumpstationer för de rika ländernas sopor. Nu har dock många av skandalerna uppdagats och vi står inför en akut situation att hantera.

Vad kan DU göra åt de växande sopbergen eller för att få fart på materialåtervinningen på riktigt?

Hur fungerar plaståtervinningen i Storbritannien?

Tusentals ton plastskrot som samlats in för återvinning från brittiska hushåll har transporterats och dumpats på platser över hela världen.

Vi följer spåret efter Storbritanniens plastavfall genom hela landet och runt om i världen. Kan Storbritannien klara sig eftersom den största importören av världens återvinning, Kina, stänger dörren?

I juli 2017 satte Kina stopp för import av plastskräp från världens länder, efter det att det visat sig att Kina använts för att dumpa icke återvinningsbara sopor från världens alla hörn.

Dokumentärfilmen ovan, producerad av Sky News 2018, tar upp problemen i Storbritannien.

Det visar sig vid granskning att endast några få procent av all plast som samlas in för återvinning verkligen återvinns! Den officiella statistiken som påstår att över 40% av plasten återvinns har inte kontrollerats, utan är bara ett mått på hur mycket av den återvinningsbara plasten som sålts och skickats iväg från landet för återvinning (som dock inte sker). Många gånger har dock sopor blandats in vilket gör återvinningen praktiskt taget omöjlig.

Men hur ser det ut i resten av världen?

Ett intressant återvinningsinitiativ i Tyskland

Tyska hushåll sorterar sitt skräp i fyra separata sopkärl med olika färger. Gul för plast, brun för kompost, blå för papper och svart för icke-återvinningsbara sopor.

I Tyskland landar två och en halv miljon ton plastförpackningar i de gula sopkärlen varje år.

Men endast 5 % av den plast som samlas in i de gula behållarna återvinns till ny plast.

Problemet är att plasten som kommer in till återvinningscentralerna är osorterad och består av en blandning av olika plastsorter som inte går att återvinna tillsammans. Det är svårt och resursintensivt (dyrt) att sortera och separera olika typer av plast, så det mesta eldas istället upp för energiåtervinning i värmekraftverk eller i stål- och cementfabriker.

I filmen ”Recycling plastics – Resource efficiency with an optimized sorting method” från VDI Resource Efficiency Center, får vi se ett exempel på cirkulär ekonomi där materialåtervinning av plast med hjälp av en optimerad sorteringsmetod ger plasten nytt liv och sluter livscykeln.

MEILO, ett företag i Gernsheim beläget i södra Hesse, sorterar plastavfall från de gula sopkärlen i 30 repetitiva sorteringsprocesser tills den maximala renheten av variation har uppnåtts. Plast separeras först efter storlek och utsätts sedan för en luftseparator. I följande steg skannar en nära infraröd skanner plasten på transportbandet när de passerar och kommunicerar till en tryckluftsstråle vid slutet av transportbandet vilken plast som kan återvinnas. Slutligen blåser tryckluftsstrålen detta material åt sidan. Således sorteras varierande plast med en upp till 98% renhet av variation. Förutom de tre viktigaste värdefulla plasten, HPDE, PP och PET, hämtas fyra andra välåtervinningsbara plastvaror från skräpfloden.

Totalt går den återvinningsbara plasten igenom sorteringsprocessen ett 30-tal gånger för att till slut nå en sorteringsgrad på upp till 98 %. Förutom de tre viktigaste värdefulla plasterna, HPDE, PP och PET, sorteras fyra andra återvinningsbara plastvaror ut bland det som ursprungligen kastats som skräp.

Problemet med att tillverka nya andra produkter av återvunnet plast är att dessa produkter ofta har en begränsad livslängd och sedan kanske inte återvinns. För ett helt cirkulärt system behöver gamla plastflaskor bli nya plastflaskor. För att detta ska kunna ske behöver den återvunna plasten processas ytterligare och göras ännu renare.

På Systec Plastics GmbH i Eisfeld, Thuringia, bearbetas plaster vidare, som sorterats av MEILO GmbH, för att producera en premiumråvara för plastindustrin. Här strimlas, rengörs och sorteras plastflingorna efter färg innan de smälts ner till granulat. De 99 % rena granulaten fylls sedan i behållare och transporteras till plasttillverkare för att bli nya produkter.

Werner & Mertz GmbH, som tillverkar tvättmedel och rengöringsmedel, använder Systec Plastics GmbH-granulat för att producera sina förpackningsflaskor. Granulatet bearbetas enkelt i Werner & Mertz GmbHs standardproduktionsanläggningar i Mainz. Deras HDPE-flaskor och PP-lock är av 100% återvunnen plast från de gula sopkärlen. Deras PET-flaskor består av 20% återvunnen PET från gula sopkärl och 80% återvunnen plast från insamlade returflaskor.

Hur ser det ut med plaståtervinningen i Sverige?

Naturvårdsverket har gjort en kartläggning av plastflöden i Sverige. Kartläggningen visar att mer material behöver materialåtervinnas. När plasten istället går till energiåtervinning bidrar den till utsläpp av växthusgaser vilket går emot Sveriges klimatmål.

Det finns dock flera tecken på en positiv utveckling, men vi har samtidigt en hel del utmaningar.

- Samlad information om Naturvårdsverkets arbete för en hållbar plastanvändning

- Rapport: Kartläggning av plastflöden i Sverige, SMED 2019 (pdf 2 MB)

Hinder för materialåtervinning

Många av de hinder för materialåtervinning som finns är gemensamma för flera typer av plastmaterial. Några av de generella hinder som utredningen Det går om vi vill – förslag till en hållbar plastanvändning (SOU 2018:84) listar som begränsar materialåtervinning av plast är:

- Svart plast är svår att sortera med IR-teknik.

- Färgad plast missfärgar övrig ofärgad plast.

- Laminat består ofta av flera olika typer av plast som sammanfogats i lager vilket försvårar återvinning.

- Nedbrytbar plast passar inte i dagens återvinningssystem.

Till dessa kan kartläggningen addera följande begränsningar:

- Begränsad sorterings- och upparbetningskapacitet (tvätt och kvarning) i Sverige.

- Begränsad efterfrågan på återvunnet material, särskilt efter Kinas importrestriktioner.

- Lågt marknadsvärde och varierande kvalitet på materialet.

- Bristande information längs värdekedjorna och över tid avseende innehåll av tillsatsämnen.

- Relativt lågt pris på jungfrulig plastråvara.

- Innehåll av ämnen som är problematiska att cirkulera

- Rapport: Ökad plaståtervinning – potential för utvalda produktgrupper

- Det går om vi vill – förslag till en hållbar plastanvändning (SOU 2018:84) (regeringen.se)

Våra vanligaste plastsorter

Plast har blivit ett allt vanligare material sedan det dök upp på marknaden för drygt 60 år sedan. Plaster kan delas in i ca 45 olika plastfamiljer och inom varje familj finns det hundratals varianter där små molekylära ändringar ger de olika plasterna varierande materialegenskaper.

Det finns flera typer av plast som är vanliga i vardagsprodukter vi har omkring oss.

Här berättar vi om de vanligaste platstyperna och hur de brukar användas.

Plast, som även kallas polymerer, består av långa molekylkedjor.

Vill du veta mer om polymerer och dess olika materialegenskaper kan du läsa den engelska artikeln ”What Is a Polymer?” på ThoughtCo, eller se filmen längst ner på denna sida.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/three-dimensional-model-of-polyvinyl-chloride-165874889-5c425ea7c9e77c000188be6d.jpg)

Härdplast och termoplast

Det två huvudgrupperna bland de många olika plastmaterialen är härdplast och termoplast.

Härdplast är plast som inte kan smältas ned eller formas om efter att den har tillverkats. Ofta använder man härdplast tillsammans med glas- eller kolfiber för större konstruktioner, såsom båtar eller segelflygplan.

Termoplast kan, till skillnad från härdplast, både smältas ned och formas om efter tillverkning. Termoplast är vanligare och några exempel på produkter av termoplast är plastpåsar, plastflaskor, glasögonbågar och mobilskal.

Polyeten (PE)

Polyeten är den vanligaste termoplasten och används framför allt i produkter som köksredskap, leksaker, rör, kablar, plastpåsar, plastfolie och flaskor. Polyeten används ofta för att det är billigt att tillverka. Polyeten är elastiskt och absorberar inte vatten samt har goda mekaniska egenskaper samt tål kontakt med många olika ämnen.

Polyeten kan ibland innehålla färgämnen och i vissa fall flamskyddsmedel vid användningar med risk för brand i till exempel kabelisolering.

Polypropen (PP)

Polypropen är en termoplast som används i produkter som matbehållare, förpackningar, leksaker, möbler och textilier. Kännetecknande för polypropen är att det är slitstarkt, genomskinligt samt tål kemiska påfrestningar, till exempel att sura livsmedel ligger länge i en förpackning.

Polypropen kan ibland innehålla färgämnen, antioxidanter och i vissa fall flamskyddsmedel vid användningar med risk för brand.

Läs Livsmedelsverkets information om plast i kontakt med mat

Polystyren (PS)

Polystyren är en vanlig och billig termoplast som förekommer i många olika typer av plastprodukter. Vanliga exempel är livsmedelsförpackningar, plastbestick, lådor för CD-skivor och värmeisoleringsmaterial. Polystyren har bra elektriska egenskaper samt är hårt och styvt.

Expanderad polystyren (XPS) används till exempel till värmeisolering.

Materialet polystyren kan innehålla mjukgörare som ftalater och organiska fosfater eller fosfatestrar. Även antioxidationsmedel, stabilisatorer och bromerade flamskyddsmedel.

Akrylnitril-Butadien-Styren (ABS)

Akrylnitril-Butadien-Styren (ABS) är en termoplast som används främst i elektroniska och tekniska produkter. Exempel är dataskärmar, tangentbord och skrivare. Typiskt för ABS är den är enkel att producera, forma samt går att variera så att den får flera olika egenskaper, till exempel att den ska vara slagtålig.

Materialet ABS kan innehålla mjukgörare som till exempel ftalater. Det kan också innehålla bromerade flamskyddsmedel, färgämnen och antioxidanter.

Polyetentereftalat (PET)

Polyetentereftalat (PET) är en av de absolut mest använda plasterna och förekommer i produkter som burkar och plastflaskor. Kännetecknande för PET är att det nästan inte väger någonting och att det är slagtåligt. PET används också i textilier och förpackningar.

Material av PET kan innehålla färgämnen.

Polymetylmetakrylat (PMMA)

Polymetylmetakrylat (PMMA), även kallat plexiglas, används ofta i till exempel baklyktor på bilar, kontaktlinser samt material som måste tåla hög påfrestning såsom akvarierutor och hockeyrinkar. PMMA är slagtåligt, splittersäkert, vädertåligt och är väldigt likt glas.

Material av PMMA kan innehålla färgämnen.

Polyamid (PA)

Polyamid (PA) förekommer mycket inom textilbranschen och är mest känt som det huvudsakliga materialet i nylonstrumpbyxor. Det används dock också i produkter som skruvar och kugghjul, köksmaskiner, fisknät och fiskelinor, bränsletankar och i elektronisk utrustning. Polyamid är färglöst men är enkelt att färga, väger inte så mycket och är tåligt.

Material av polyamid kan innehålla färgämnen.

Polyvinylklorid (PVC)

Polyvinylklorid (PVC) är den tredje mest använda plasten i världen efter polypropen och polyeten. PVC är i grunden en så kallad styv plast, alltså att den är hård.

Styv PVC används mycket i vatten- och avloppsrör och hårda platsleksaker. Mjukgjord PVC, alltså när man tillsatt mjukgörare i plasten, används till exempel i slangar, golv, höljen till elektriska kablar, tryck på kläder, i regnkläder, skor, väskor och bälten samt i mjuka plastleksaker och i sjukvårdsmaterial som stomi- och blodpåsar. PVC är också den plast som användes i samt gav namnet till vinylskivor.

Merparten av de mjukgörare som används i plastmaterial går till tillverkningen av mjuk PVC.

Material av PVC kan innehålla färgämnen, mjukgörare, stabilisatorer och ibland flamskyddsmedel.

Polykarbonat (PC)

Polykarbonat används i produkter som till exempel CD-skivor, glasögon och trafiklampor. Polykarbonat används också till skottsäkra fönster samt till visir, maskinskydd och flygplansfönster. Typiskt för polykarbonat är att det är genomskinligt, är slag- och värmetåligt samt är elektriskt isolerande.

Polykarbonat kan innehålla tillsatser som mjukgörare, bromerade flamskyddsmedel, färgämnen och antioxidanter.

Gummimaterial

Plastmaterial inkluderar även gummimaterial. Gummi består liksom plast av en eller flera polymerer och en rad olika tillsatsämnen och kännetecknas av sina elastiska egenskaper. Polymeren kan antingen vara naturlig eller syntetisk. Beroende på val av polymer och tillsatsämnen får gummimaterialen olika egenskaper, från mjuka till hårda och styva material. Exempel på tillsatsämnen i gummimaterial är, antioxidanter, UV-strålningsskydd, fyllmedel, mjukgörare och stabilisatorer. Den största enskilda produkten där gummi används är gummidäck.

Läs om konstgräs av återvunna gummidäck.

Epoxi

Icke-förstärkt epoxi kan användas i fogmassa och ytbeläggningar, speciellt på stål och betong. Fiberförstärkt epoxi används för delar i bilar, båtar och flygplan, bränsletankar, golv och komponenter i elektronik.

Epoxi är en värmehärdande plast som har hög resistens mot lösningsmedel och basiska ämnen samt har bra motstånd mot slitage. Epoxi har också goda elektriska och mekaniska egenskaper.

Material av epoxi kan innehålla färgämnen och flamskyddsmedel. Bisfenol A används vid tillverkningen av epoxi och därför kan material av epoxi innehålla bisfenol A som en rest.

Polyuretan (PUR)

I de flesta fall används polyuretan (PUR) som skum i isolering för fjärrvärmerör, kylskåp och frysar samt till möbler, madrasser, golv och skor. Styvt skum av PUR används bland annat till fordonsdelar för till exempel stötfångare.

Material av PUR kan innehålla flamskyddsmedel och biocider.

Polytetrafluoretylen (PTFE)

PTFE har fysikaliska egenskaper som gör den mycket hal (låg friktion). Materialet är känt från varumärken som till exempel Teflon och Gore-Tex.

PTFE är kemikaliebeständigt och kan användas inom ett brett temperaturområde. Det har bra elektriska egenskaper och har en vaxliknande yta som praktiskt taget inget häftar på. Det absorberar inte vatten och bryts inte ner av UV-ljus, ozon eller syre till skillnad från andra termoplaster.

PTFE används i till exempel i stekpannor för att hindra maten från att bränna fast. PTFE används även som slitlager i olika former av glidlager och liknande där man vill ha en låg friktion. Medicinskt används PTFE till exempel i implantat. De goda kemiska egenskaperna gör att ett implantat har lång livstid. Inom optiken kan PTFE-plast användas i vissa typer av linser, eftersom det är transparent för infrarött ljus.

Källa: Kemikalieinspektionen

Återvinning av plast

Återvinningssymboler, till exempel en triangel med siffra inuti, anger huvudplasten i produkten. Denna typ av symboler har sitt ursprung i EUs förpackningsdirektiv och om förpackningsavfall och är frivillig och är inte en del av livsmedelslagstiftningen eller har med Livsmedelsverkets ansvar att göra. Dessa symboler har heller inget med säkerhet hos materialet att göra.

| Siffra i återvinnings- triangeln | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasttyp | PET | PE-HD | PVC | PE-LD | PP | PS | O*) |

* andra plaster; till exempel polykarbonat (PC)

Mer information om polymerer

Table of Contents (Polymers: Crash Course Chemistry #45):

Commercial Polymers & Saved Elephants 0:00

Ethene AKA Ethylene 2:29

Addition Reactions 3:08

Ethene Based Polymers 4:44

Addition Polymerization & Condensation Reactions 6:32

Proteins & Other Natural Polymers 8:33

Spela ett interaktivt spel om polymerer.

Konfigurera Raspberry Pi som en nätverksrouter

Bygga en egen autonom bil – The Batmobile

Test driving the Batmobile

The thrill of taking a corner, extremely low to the ground, with your gut telling you these g-forces are not normal… that’s why we spend countless hours building these silly Power Wheels vehicles. The giggles and grins are unavoidable! These cars are so much fun to drive — and even more fun to race!

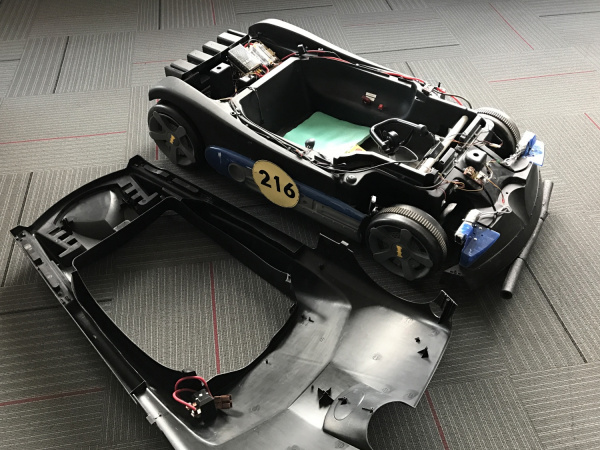

In 2016, SparkFun had its eighth annual Autonomous Vehicle Competition. This year saw the introduction of a new rule: you needed to carry a human (or a 20lb dead weight in the form of a watermelon if you were too chicken). To do this, my wife, Alicia, and I modified a Batmobile Power Wheels and combined it with a Razor chassis. The result was an extremely zippy electric go-kart that left a perma-grin on everyone who drove it.

Our goal was to create a vehicle that could quickly and easily switch between human driver and driverless modes so that we could compete in both PRS and A+PRS categories. In the end, Alicia placed a very respectable third place in the driver category, and I did not finish (DNF) in the autonomous category, running into numerous hay bales.

This tutorial attempts to document a six-month build process for an Autonomous + Power Racing Series (A+PRS) vehicle. Every autonomous vehicle is unique, and the requirements of each will vary from build to build.

Materials

You can see our overall budget, including a list of components and vendors here.A+PRS BATMOBILE MATERIAL SPREADSHEET

You can get all the code from our repo here.A+PRS BATMOBILE GITHUB REPOSITORY

Chassis

The AVC rules stipulate that you cannot spend more than $500 on your total budget and that you have to stay within certain size restrictions. We started trolling craigslist to see what was out there and immediately found a plethora of free or cheap “broken” Power Wheels. When a Batmobile for $25 popped up, we quickly snagged it.

Dusty with dog hair and dead spiders — it’s perfect!

The primary failure of all used Power Wheels is a dead battery. The Batmobile was no different; as soon as we put in a new 12V SLA (Sealed Lead Acid), it happily, albeit slowly, drove around. There is nothing magical about “Power Wheels” branded batteries; get the right voltage (usually 12V, sometimes 6V), and you can use almost any battery you’d like.

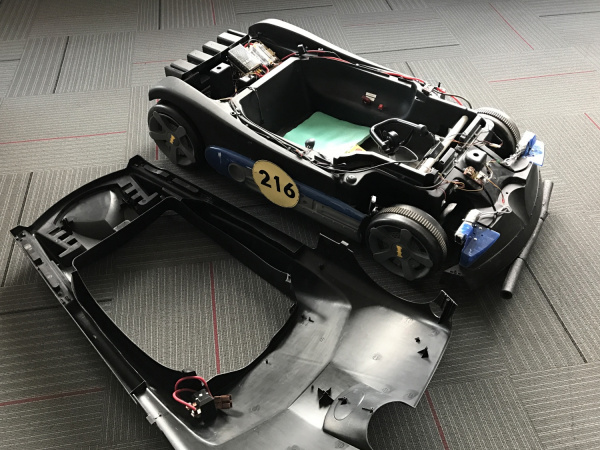

The original batmobile chassis blow molded plastic at its finest. The wheels are hollow, the motor is designed to move a child slowly (and reasonably safely), and the steering is littered with bits of metal but mostly loose and wobbly. While the stock chassis was capable of moving adults weighing in at around 200lbs, we knew it wouldn’t handle racing, so we decided to find a metal chassis to sit underneath.

Note the size of the motor and battery. Those are about to get much larger.

Razor is known for their kick scooters, but they’re in the electric go-kart market as well. We found a Razor Drifter Open Box for $165. The Drifter had the steering, brakes, wheels and chassis sorted out for us! Additionally, the Drifter came with a stock 24V battery, 250W motor and 250W motor controller.

Many PRS and AVC competitors are talented enough to weld their own chassis together. DIY welding is a great way to save money, but it may take weeks of fabrication. Because we planned to enter the autonomous field, we decided to find a ready-made chassis and spend our time building and debugging the autonomous bits.

Putting on a Hat

Once we had the Power Wheels and the Razor chassis, we had to combine the two.

We slid the razor chassis underneath the plastic batmobile shell. The razor chassis has strength where we needed it most: steering, chassis, brakes, drive train, everything. The plastic batmobile is just there as a shell. The four solid plastic+rubber razor wheels make contact with the ground. The four hollow batmobile wheels hover above the ground and are there only for cosmetic looks (for the lulz).

A Power Wheels meets a Drifter

At some point you have to get out the reciprocating saw and severely modify your beautiful Power Wheels. We laid the Batmobile over the Razor and proceeded to chop off all the bits that got in the way.

Bare metal chassis before shell is laid on top

Seats? Where we’re going, we don’t need seats!

Pleasingly, the Batmobile sits on top of the chassis under its own structural support. We didn’t need to add all-thread or other standoffs. Even though they don’t do anything, we reattached the original wheels just so it looked extra wacky.

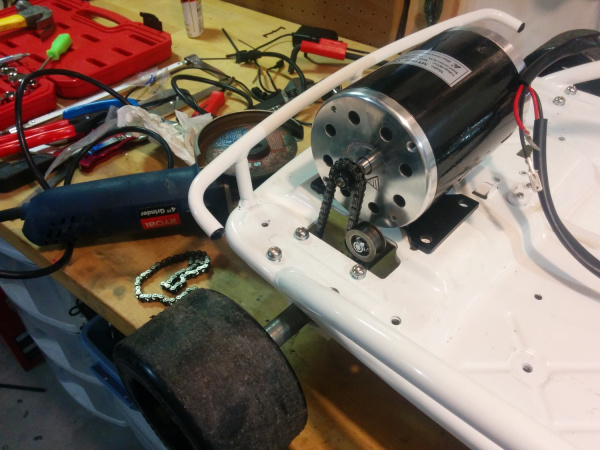

Motor and Motor Control

Moar!

In 2016, A+PRS allowed 48V systems, so the first thing we did was remove the 24V motor and install a 1,000W 48V/21A motor. The PRS rules limit any system to 1,400W, so we could have gone larger had budget constraints not been kicking in fast. New mounting holes were drilled into the chassis, and a different gear had to be mounted to the end of the motor. But it all went well. The stock chassis even included a chain tensioner that proved invaluable!

The MY1020 48V motor we used is common on the PRS circuit and performed great. However, our original 1,000W motor controller (you should already be able to tell what’s coming) did not do so well. Our first tests of the 48V system in an open parking lot worked great until the motor controller overheated and failed. And when MOSFET-based motor controllers fail, they fail unsafe, meaning our vehicle decided to go to 100 percent throttle and stay there. This is why we have safety switches! Alicia and I were able to kill the vehicle before anyone got hurt.

This failure should have been prevented: a motor controller should be rated for at least 2 times what you calculate your maximum load will be. In our case, if we wanted to control a 1kW motor, we should have been using a motor controller rated to a constant 2kW load. Luckily, the A+PRS rules don’t require you to record how much money you spent (and burned up); you have to report only what is on the vehicle as it rolls on race day.

The new, larger 5kW motor controller

We quickly located a larger, 5kW motor controller (this one even had reverse!) and got it on order. This larger motor controller has been working swimmingly ever since. Find a motor controller with reverse. You’ll be tempted to drive your souped-up Power Wheels in weird places (like the SparkFun inventory aisles), and a reverse gear allows for hilarious 5-point turns.

Brakes

Go-kart drum brakes on eBay

The Razor chassis had the classic drum brake, perhaps the weakest link of the Razor. While the stock brake was probably the appropriate size for a 75lb child with stock 24V batteries, our brakes got really squishy once we added an additional 125lbs of meat bag, batteries and plastic bits. We rarely, if ever, used the brakes during races, but the PRS rules stipulate that your qualifying lap must end with the driver crossing the finish line and braking to a stop:

At the end of the hot lap, your car will have to come to a complete stop within 18ft of when its transponder crossed the start/finish line. Deliberately skidding, swerving or spinning out is not an acceptable method of braking for the brake test.

Alicia had to do an impressive combination of hard braking, swerving, skidding and sliding with such a dramatic flair that she wooed the judges into not noticing how dodgy our brakes were. We’ll have disc brakes installed before we roll in the 2017 race.

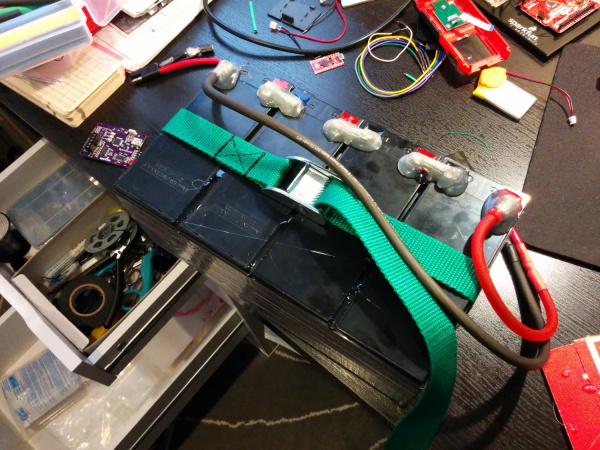

Batteries

Battery holder welded onto the front of the chassis

As part of the motor upgrade, we needed to increase the battery voltage to 48V. To save money, we reused the super common batteries that came with the 24V Razor chassis. Razor was smart; they looked at the SLA (Sealed Lead Acid) battery industry and picked the most common size. This just happened to be the same battery that goes into nearly every UPS on the planet. We purchased two additional UPS-size batteries (way cheaper than buying Razor-brand batteries) and wired them in series.

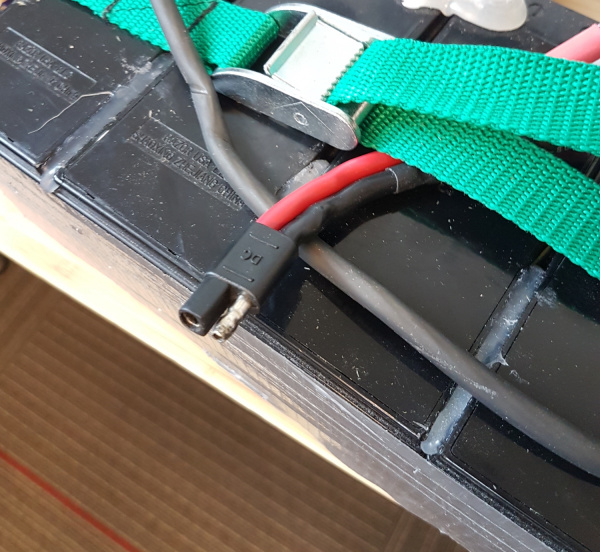

Four batteries combined in series

Taping the cells together and adding a bead of hot glue between the cells made the pack nicely rigid. A low-cost, polarized, high-current connector finished off the pack. We had an old strap lying around that made all the difference in the world; it’s a lot more comfortable carrying the pack one-handed by its handle than with two hands underneath.

Avoid fires and other bad things. Use polarized connectors for your batteries.

Wire

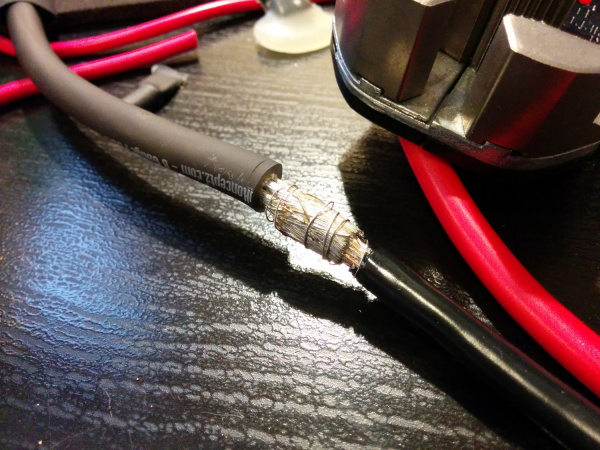

Soldering large-gauge wire

We originally spec’d out some really nice, super flexible silicone-sheathed 8AWG wire for power distribution. I don’t think we would do this again; 10AWG would have been fine, and probably even 12AWG. As 8-gauge is far less common, the wire and connectors are more expensive, and the larger gauge wire takes a lot more soldering heat — it’s just a pain to work with. If you need the current capacity, go for it, but for our extremely zippy, 48V 20A vehicle, 8-gauge wire was overkill.

If you decide to use super flexible, large gauge wire, spend some time on the internet reading about how to solder this type of wire.

The best technique I found:

- Make sure you’ve got heat shrink in place

- Turn your soldering iron up to 425C (way hotter than the 325C usually needed)

- Push the ends of wire together

- Wrap tightly with 30AWG wire wrap wire

- Liberally apply flux

- Heat and insert lots of solder until the joint turns silver

Here’s a good video demonstrating this technique:

Kill Switch

We documented how to build a wireless kill switch while making margaritas. It was a ton of fun, so we’ll skip the bits of the wireless kill switch system here.

Zroooommmm!

In addition to the wireless disconnect, we had a large, red mushroom kill switch that disconnected the battery with a pleasing and authoritative ”thunk.” Pulling up on the mushroom button reconnects the battery to the system.

Batman logo or Bitman logo?

As a pleasant bonus feature, the mushroom kill switch got rid of the nasty sparks. When connecting the battery to the motor controller, there was such an inrush of current into the capacitors and electronics that the connector would spark. Once we got the kill switch installed, we could connect/disconnect batteries without these sparks.

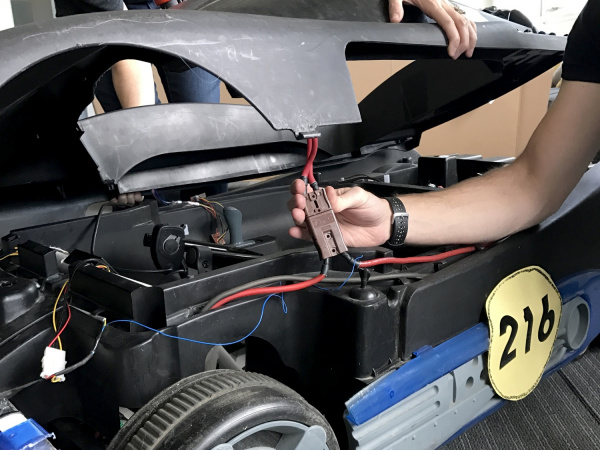

Connector between kill switch and power bus

The top of the Batmobile was easily removed, but because it had the kill switch installed we needed a way to disconnect it easily from the power bus. We found a great high-power connector in a dead server UPS. These are often called ”winch connectors”, because they are higher current. With this connector, we are able to quickly disconnect the kill switch and remove the top when we need to get at the inside of the vehicle.

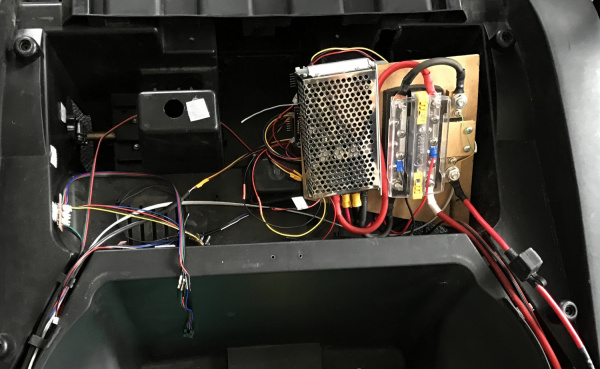

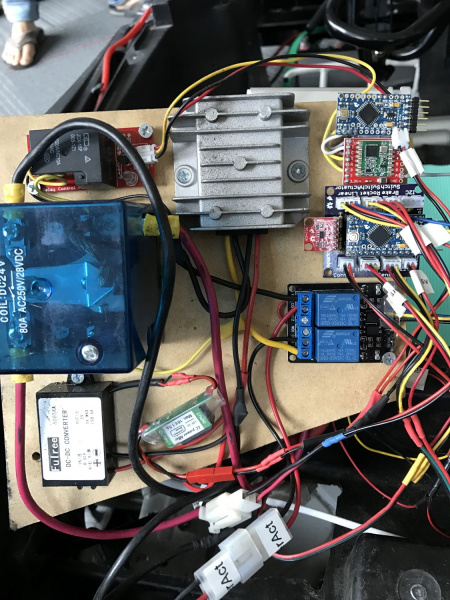

Control Electronics

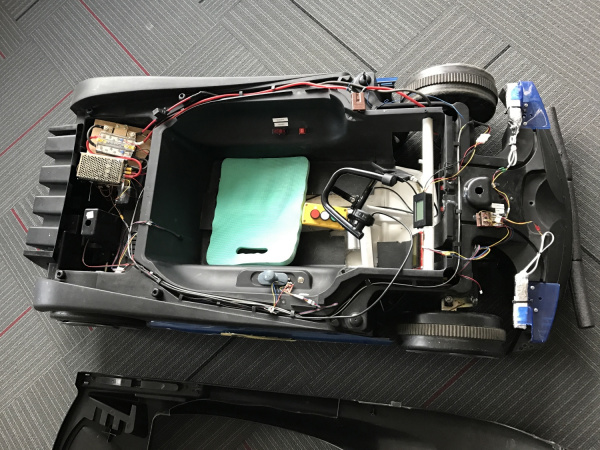

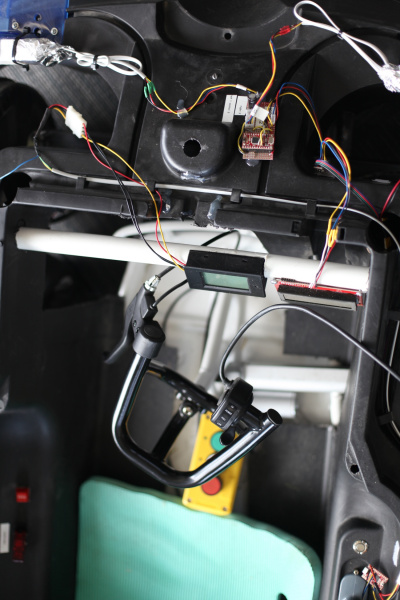

Power converters, motor kill relays, steering relays, locomotion controller and wireless communication

The control electronics are complex. We had a total of seven microcontrollers on this beast, plus three used in the distance sensors for a total of 216 bits of processing power. The system operated on an I2C bus with the brain sending commands to the locomotion controller and LCD and receiving data from the sensors.

The wiring underneath the Batmobile cover

For a previous 2010 AVC entry, I did everything on a single microcontroller. This made coding and debugging a challenge. On our 2016 entry, we focused each sub-system to do one thing very well.

The subsystems are broken down as follows:

- Brain Controller: A SAMD21 Mini was used to communicate with and process all the data from the distance sensors, GPS and compass, and to send out commands to control throttle and steering. It monitored a start switch and relayed debug information to an LCD.

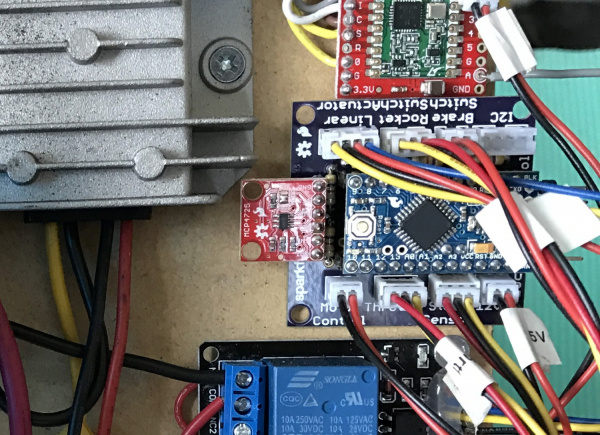

- Locomotion Controller: An Arduino Pro Mini read the throttle, steering position, brake switch and autonomous rocket switch. It controlled motor speed and the linear actuator for steering.

- Wireless Kill Switch: An Arduino Pro Mini lived in the wireless kill switch, a requirement for the autonomous part of our Batmobile. To learn more about the wireless controller, check out our tutorial on how to build a wireless kill switch.

- A dedicated Arduino Pro Mini controlled the relays for the wireless kill switch system.

- Debug LCD: We counted our LCD screen as a microcontroller since it has an Arduino in it.

- Sensor Combinator: A SAMD21 Mini polled the serial GPS and I2C compass.

- Laser Controller: A SAMD21 Mini controlled the three serial-based laser distance sensors, combined the relevant information and responded to requests from the Brain.

- Three STM32s were the brains within the laser distance sensors.

Interested in learning more about distance sensing?

Learn all about the different technologies distance sensors use and which products would work best for you next project.TAKE ME THERE!

Control Electronics – Brain

The Brain is a SAMD21 Mini. It sends commands over the I2C bus to the locomotion controller and debug LCD.

4-pin JST connector at the top of the image: We used a 4-wire bus (5V, GND, SDA, SCL) for communication and had various taps throughout the bus to allow devices to be attached. This worked really well and allowed for devices to be moved around when needed.

4-pin JST connector to the left: This was four wires to the button. To tell the vehicle to begin navigating under autonomous control, we used a metal momentary push button that illuminates when everything is online and happy. The human presses the button twice, and the car commences racing.

Big gray handle: This was the original forward and reverse knob that we reused to control the direction switch on the motor controller (two pins when shorted together caused one direction, when open caused the other direction).

The massive and poorly written control code for the Brain can be found here.

EEPROM for Waypoints

The SAMD21 does not have internal EEPROM. Because we needed to store GPS waypoints and other configuration data to non-volatile memory, we used an external I2C EEPROM. Yes, you can use something called emulated EEPROM on the SAMD21, but, every time you reprogram the board, you will overwrite anything previously stored in emulated EEPROM. The external EEPROM made it much easier to store and recall waypoints and settings without having to mash together in the main control code.

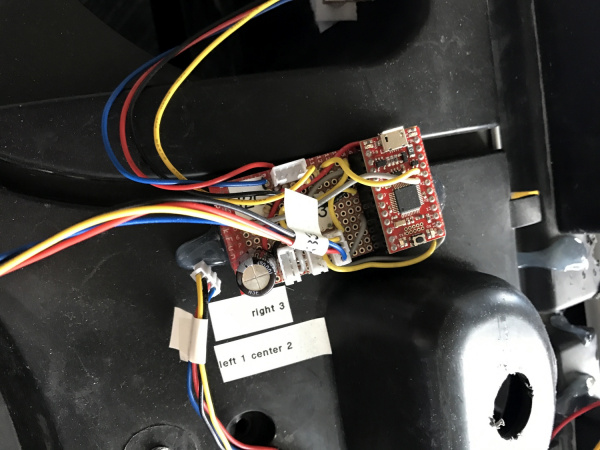

Control Electronics – Locomotion

Locomotion Controller hooked up

Note the polarized connectors and prodigious labeling! You DO NOT want to be guessing what gets plugged into where at 11 p.m. before race day. The Locomotion Controller code is available here, and the PCB layout here.

Because we eventually wanted this beast to be autonomous, we needed to put a controller in the middle between the throttle and the motor controller. We used an Arduino Pro Mini that did a huge variety of sensing and control:

- Read the throttle

- Output analog voltage to the motor controller

- Read the brake switch

- Read the steering position

- Controlled the linear steering actuator

- Read the human/robot control switch

- Received and responded to control commands over I2C

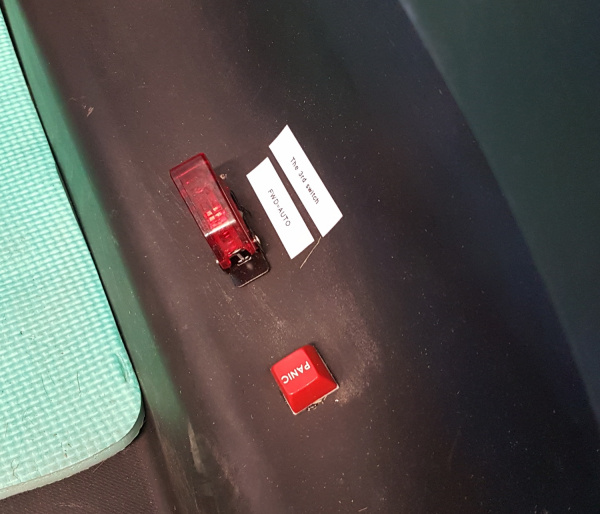

Don’t panic

The controller would monitor the rocket switch and brake switch. If a human ever pressed the brakes or turned off the rocket switch, the controller would go into safety shutdown and ignore any commands from the brain.

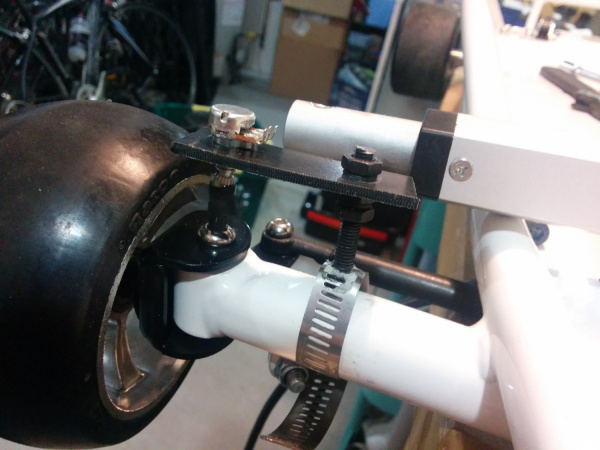

Steering was controlled using a 12V linear actuator over-voltaged to 24V for extra speed. Two relays controlled the forward/backward motion.

Steering position was obtained by cutting a hex wrench to about 1” and inserting that wrench into the bolt that rotates with the wheel. The wrench was then connected to a 10k trimpot using adhesive-lined heat shrink — this trick is known as the ”poor man’s coupler:” a 3-wire ribbon connected the trimpot back to the locomotion controller. It worked well, but we had to keep the analog signal wire away from the power bus; otherwise, bad noise got into the ADC readings.

Chassis with the Batmobile raised to see the steering actuator

For future vehicles, we’re going to change this setup. It worked well enough, but once the bolt connected the actuator to the steering, you couldn’t drive the car; only the computer could. So rather than driving the car to the start line, we had to carry this 75lb beast. So painful. In the future, we plan to find a back-drivable actuator or maybe drive-by-wire.

Control Electronics – Displays

Throttle and displays

We cut notches in a 1” tube of PVC and mounted two displays in the Batmobile. The center display is the power meter. Nearly every A+PRS and PRS competitor used these super low-cost power meters to show the battery voltage. We had some issues with it, but it worked well enough. In the end, we noticed the drop in vehicle speed (indicating battery drain) long before we noticed the display was indicating a lower pack voltage. But, it did help us make decisions about when to pit (never!) because the nominal 48V pack voltage was dropping down to 42V where we could begin to damage the SLA.

The display on the right is the 20×4 character debug LCD. It’s basically a souped-up version of our 20×4 SerLCD display (it’s a prototype product, coming soon to a theater near you!).

Control Electronics – Sensors

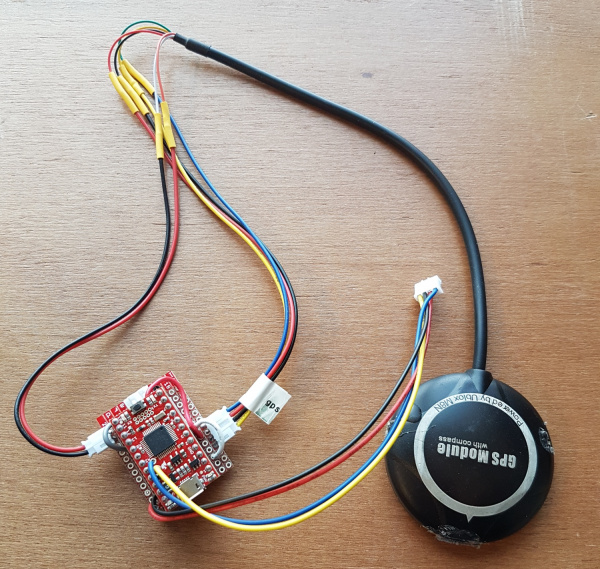

GPS+Compass connected to SAMD21

The Sensor Combinator is a SAMD21 Mini that monitors a GPS receiver and an I2C compass. We decided to use a SAMD21 because it can be configured to have multiple hardware serial and I2C ports. This is needed if you want to isolate I2C devices from the main bus. We wanted the Brain to ask for the heading and get the heading; the Sensor Combinator took care of the low-level I2C function of the compass and heading calculations. Similarly, the Combinator listened to the serial stream from the u-blox based GPS module and parsed out all the needed Latitude/Longitude/SIV information.

The code for the Sensor Combinator can be found here.

Control Electronics – Lasers

Laser tape measures seen on the front of the car, wrapped in foil

We hacked three laser tape measures in order to get distance to any objection front, left or right of the car. Laser tape measures are getting cheaper, and while the read rate (3Hz at the best of times) is not great for LIDAR, it’s fast enough for basic, low-cost autonomy.

Laser Controller at front of car

Unfortunately, the laser tape measures threw off enough RF to interfere with our GPS module, so we wrapped the lasers in foil. These sensors deserve their own tutorial, which will be written soon.

Laser Controller with labels

Again we chose the SAMD21 Mini to help us control and combine the serial information coming from the three sensors. The Laser Controller would send the pertinent control strings to the tape measures and monitor the responses, combining them into distances for left/right/center. The Brain would request these values from the Laser Controller over I2C.

Note the prodigious amounts of labels and polarized connectors (JSTs work great!). This system required lots of debugging but worked well because we were able to quickly disconnect and reconnect various aspects of the system.

The code for the Laser Controller can be found here.

Problems

As with any project, we had a large number of problems and hurdles to overcome along the way. Here are a few that really hurt.

** EMI and GPS **

The Laser tape measures caused significant interference with GPS reception. We eventually moved the GPS module to the rear of the car, which improved positional accuracy. However, the motor caused interference with the compass.

** DC Motor EMF **

DC motors produce a ton of electromagnetic noise. We originally had the 48V battery powering the entire car. However, when the motor would kick on, it would cause enough ripple to make the Brain glitch and reset. We tried powering the I2C bus separately, but, because the Locomotion Controller needed to be attached to the motor controller, a GND connection had to be shared. The noise eventually found its way over the I2C bus. In the future we will optically isolate the I2C bus.

** Lack of EEPROM **

Because the SAMD21 doesn’t have internal EEPROM, we were unable to store GPS waypoints on the board. We fixed this by using an I2C-based EEPROM.

** Switching Steering Between Driver/Driverless **

It was difficult to attach and detach the linear actuator from the rack and pinion steering. Once the actuator was attached to the steering, a driver could not actively steer (for example, to the starting line). This could be fixed with a different actuator that could be back-driven, or we could go full monty and detach the steering column from the steering and have it control a trimpot that, in turn, controls the linear actuator (drive by wire).

Tips / Best Practices

Tip 1) Start early — These vehicles take a large amount of time. Get together with friends and start hacking. It’s a great labor of love, and drifting in a 15mph go-kart will make you giggle.

Tip 2) Get reverse — Get a motor controller with reverse. It will make it so you can drive your car where you want it instead of carrying your car where you need it.

Tip 3) Use connectors! — I’ve written about using connectors a few times. Use polarized connectors and a label maker to make it clear what plugs in where.

Tip 4) Size your motor and motor controller correctly — We blew our motor controller because it was underrated. A friend of ours smoked his motor because he was pushing too much current. Pick your system voltage and current, and then double the ratings wherever you can.

Tip 5) Beware of interference — These vehicles can pull 30 amps or more when accelerating, which can cause large electromagnetic fields. Keep unshielded cables and sensitive sensors away from power wires.

Tip 6) Wireless control and sensor logging — After you pick up your 75lb vehicle and drag it to the start line for the fifth time, you’ll understand the need for remote control. Create a wireless system that allows you to take over control of the vehicle from afar so you can drive it where you need it. And transmit the sensor data so you can see what the vehicle is doing.

Python och GPS-spårning

Detta är en artikel från SparkFun, December 17, 2012

Introduction

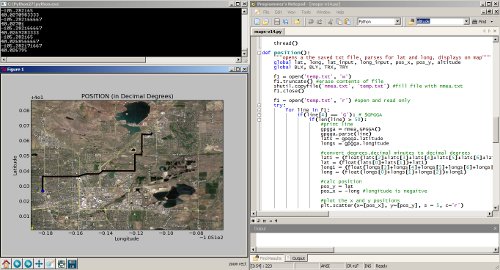

In my quest to design a radio tracking system for my next HAB, I found it very easy to create applications on my computer and interact with embedded hardware over a serial port using the Python programming language. My goal was to have my HAB transmit GPS data (as well as other sensor data) over RF, to a base station, and graphically display position and altitude on a map. My base station is a radio receiver connected to my laptop over a serial to USB connection. However, in this tutorial, instead of using radios, we will use a GPS tethered to your computer over USB, as a proof of concept.

Of course, with an internet connection, I could easily load my waypoints into many different online tools to view my position on a map, but I didn’t want to rely on internet coverage. I wanted the position of the balloon plotted on my own map, so that I could actively track, without the need for internet or paper maps. The program can also be used as a general purpose NMEA parser, that will plot positions on a map of your choice. Just enter your NMEA data into a text file and the program will do the rest.

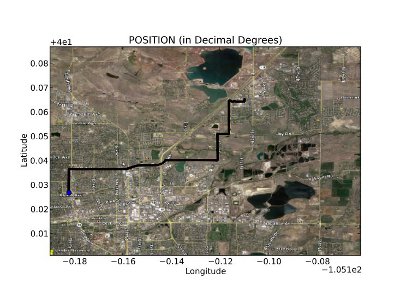

Showing a trip from SparkFun to Boulder, CO.

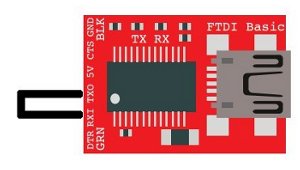

This tutorial will start with a general introduction to Python and Python programming. Once you can run a simple Python script, we move to an example that shows you how to perform a serial loop back test, by creating a stripped down serial terminal program. The loopback test demonstrates how to send and receive serial data through Python, which is the first step to interacting with all kinds of embedded hardware over the serial port. We will finish with a real-world example that takes GPS data over the serial port and plots position overlaid on a scaled map of your choice. If you want to follow along with everything in this tutorial, there are a few pieces of hardware you will need.

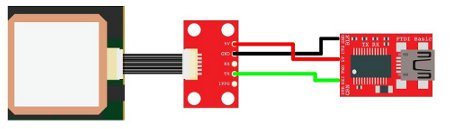

- 5V FTDI Basic

- EM-406 GPS module with Breakout Board (or any NMEA capable GPS)

For the loopback test, all you need is the FTDI Basic. For the GPS tracking example, you will need a GPS unit, as well as the FTDI.

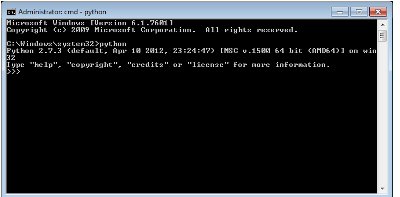

What is Python?

If you are already familiar with installing and running Python, feel free to skip ahead. Python is an interpreted programming language, which is slightly different than something like Arduino or programming in C. The program you write isn’t compiled as a whole, into machine code, rather each line of the program is sequentially fed into something called a Python interpreter. Once you get the Python interpreter installed, you can write scripts using any text editor. Your program is run by simply calling your Python script and, line by line, your code is fed into the interpreter. If your code has a mistake, the interpreter will stop at that line and give you an error code, along with the line number of the error.

The holy grail for Python 2.7 reference can be found here:

Installing Python

At the time of this tutorial, Python 2.7 is the most widely used version of Python and has the most compatible libraries (aka modules). Python 3 is available, but I suggest sticking with 2.7, if you want the greatest compatibility.

After you install Python, you should be able to open a command prompt within any directory and type ’python’. You should see the interpreter fire up.

If you don’t see this, it is time to start some detective work. Copy your error code, enter it into your search engine along with the name ’python’ and your OS name, and then you should see a wealth of solutions to issues similar, if not exact, to yours. Very likely, if the command ’python’ is not found, you will need to edit your PATH variables. More information on this can be found here. FYI, be VERY careful editing PATH variables. If you don’t do it correctly, you can really mess up your computer, so follow the instructions exactly. You have been warned.

If you don’t want to edit PATH variables, you can always run Python.exe directly out of your Python installation folder.

Running a Python Script

Once you can invoke the Python interpreter, you can now run a simple test script. Now is a good time to choose a text editor, preferably one that knows you are writing Python code. In Windows, I suggest Programmers Notepad, and in Mac/Linux I use gedit. One of the main rules you need to follow when writing Python code is that code chunks are not enclosed by brackets {}, like they are in C programming. Instead, Python uses tabs to separate code blocks, specifically 4 space tabs. If you don’t use 4 space tabs or don’t use an editor that tabs correctly, you could get errant formatting, the interpreter will throw errors, and you will no doubt have a bad time.

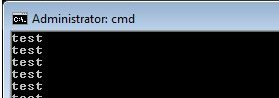

For example, here is a simple script that will print ’test’ continuously.

# simple script

def test():

print "test"

while 1:

test()

Now save this code in a text editor with the extention your_script_name.py.

The first line is a comment (text that isn’t executed) and can be created by using a # .

The second line is a function definition named test().

The third line is spaced 4 times and is the function body, which just prints ”test” to the command window.

The third line is where the code starts in a while loop, running the test() function.

To run this script, copy and paste the code into a file and save it with the extention .py. Now open a command line in the directory of your script and type:

python your_script_name.py

The window should see the word ’test’ screaming by.

To stop the program, hit Ctrl+c or close the window.

Installing a Python Module

At some point in your development, you will want to use a library or module that someone else has written. There is a simple process of installing Python modules. The first one we want to install is pyserial.

Download the tar.gz file and un-compress it to an accessible location. Open a command prompt in the location of the pyserial directory and send the command (use sudo if using linux):

python setup.py install

You should see a bunch of action in the command window and hopefully no errors. All this process is doing is moving some files into your main Python installation location, so that when you call the module in your script, Python knows where to find it. You can actually delete the module folder and tar.gz file when you are done, since the relevant source code was just copied to a location in your main Python directory. More information on how this works can be found here:

FYI, many Python modules can be found in Windows .exe installation packages that allow you to forgo the above steps for a ’one-click’ installation. A good resource for Windows binary files for 32-bit and 64-bit OS can be found here:

Python Serial Loopback Test

This example requires using an FTDI Basic or any other serial COM port device.

Simply, connect the TX pin to the RX pin with a wire to form a loopback. Anything that gets sent out of the serial port transmit pin gets bounced back to the receive pin. This test proves your serial device works and that you can send and receive data.

Now, plug your FTDI Basic into your computer and find your COM port number. We can see a list of available ports by typing this:

python -m serial.tools.list_ports

If you are using linux:

dmesg | grep tty

Note your COM port number.

Now download the piece of code below and open it in a text editor (make sure everything is tabbed in 4 space intervals!!):

import serial

#####Global Variables######################################

#be sure to declare the variable as 'global var' in the fxn

ser = 0

#####FUNCTIONS#############################################

#initialize serial connection

def init_serial():

COMNUM = 9 #set you COM port # here

global ser #must be declared in each fxn used

ser = serial.Serial()

ser.baudrate = 9600

ser.port = COMNUM - 1 #starts at 0, so subtract 1

#ser.port = '/dev/ttyUSB0' #uncomment for linux

#you must specify a timeout (in seconds) so that the

# serial port doesn't hang

ser.timeout = 1

ser.open() #open the serial port

# print port open or closed

if ser.isOpen():

print 'Open: ' + ser.portstr

#####SETUP################################################

#this is a good spot to run your initializations

init_serial()

#####MAIN LOOP############################################

while 1:

#prints what is sent in on the serial port

temp = raw_input('Type what you want to send, hit enter:\n\r')

ser.write(temp) #write to the serial port

bytes = ser.readline() #reads in bytes followed by a newline

print 'You sent: ' + bytes #print to the console

break #jump out of loop

#hit ctr-c to close python window

First thing you need to do before running this code is to change the COM port number to the one that is attached to your FTDI. The COMNUM variable in the first few lines is where you enter your COM port number. If you are running linux, read the comments above for ser.port.

Now, if you want to send data over the serial port, use:

ser.write(your_data)

your_data can be one byte or multiple bytes.

If you want to receive data over the serial port, use:

your_data = ser.readline()

The readline() function will read in a series of bytes terminated with a new line character (i.e. typing something then hitting enter on your keyboard). This works great with GPS, because each GPS NMEA sentence is terminated with a newline. For more information on how to use pyserial, look here.

You might realize that there are three communication channels being used:

- ser.write – writes or transmitts data out of the serial port

- ser.read – reads or receives data from the serial port

- print – prints to the console window

Just be aware that ’print’ does not mean print out to the serial port, it prints to the console window.

Notice, we don’t define the type of variables (i.e. int i = 0). This is because Python treats all variables like strings, which makes parsing text/data very easy. If you need to make calculations, you will need to type cast your variables as floats. An example of this is in the GPS tracking section below.

Now try to run the script by typing (remember you need to be working out of the directory of the pythonGPS.py file):

python pythonGPS.py

This script will open a port and display the port number, then wait for you to enter a string followed by the enter key. If the loopback was successful, you should see what you sent and the program should end with a Python prompt >>>.

To close the window after successfully running, hit Ctrl + c.

Congratulations! You have just made yourself a very simple serial terminal program that can transmit and receive data!

Read a GPS and plot position with Python

Now that we know how to run a python script and open a serial port, there are many things you can do to create computer applications that communicate with embedded hardware. In this example, I am going to show you a program that reads GPS data over a serial port, saves the data to a txt file; then the data is read from the txt file, parsed, and plotted on a map.

There are a few steps that need to be followed in order for this program to work.Install the modules in the order below.

Install modules

Use the same module installation process as above or find an executable package.

- pyserial (should already be installed from above)

- numpy (use: this link for Windows and this link for Mac/Linux)

- matplotlib

- pynmea

The above process worked for me on my W7 machine, but I had to do some extra steps to get it to work on Ubuntu. Same might be said about Macs. With Ubuntu, you will need to completely clean your system of numpy, then build the source for numpy and matplotlib separately, so that you don’t mess up all of the dependencies. Here is the process I used for Ubuntu.

Once you have all of these modules installed without errors, you can download my project from github and run the program with a pre-loaded map and GPS NMEA data to see how it works:

Or you can proceed and create your own map and GPS NMEA data.

Select a map

Any map image will work, all you need to know are the bottom left and top right coordinates of the image. The map I used was a screen shot from Google Earth. I set placemarks at each corner and noted the latitude and longitude of each corner. Be sure to use decimal degrees coordinates.

Then I cropped the image around the two points using gimp. The more accurate you crop the image the more accurate your tracking will be. Save the image as ’map.png’ and keep it to the side for now.

Hardware Setup

The hardware for this example includes a FTDI Basic and any NMEA capable GPS unit.

EM-406 GPS connected to a FTDI Basic

For the connections, all you need to do is power the GPS with the FTDI basic (3.3V or 5V and GND), then connect the TX pin of the GPS to the RX pin on the FTDI Basic.

It is probably best to allow the GPS to get a lock by leaving it powered for a few minutes before running the program. If the GPS doesn’t have a lock when you run the program, the maps will not be generated and you will see the raw NMEA data streaming in the console window. If you don’t have a GPS connected and you try to run the program, you will get out-of-bound errors from the parsing. You can verify your GPS is working correctly by opening a serial terminal program.

Run the program

Here is the main GPS tracking program file:

Save the python script into a folder and drop your map.png file along side maps.py. Here is what your program directory should look like if you have a GPS connected:

The nmea.txt file will automatically be created if you have your GPS connected. If you don’t have a GPS connected and you already have NMEA sentences to be displayed, create a file called ’nmea.txt’ and drop the data into the file.

Now open maps.py, we will need to edit some variables, so that your map image will scale correctly.

Edit these variables specific to the top right and bottom left corners of your map. Don’t forget to use decimal degree units!

#adjust these values based on your location and map, lat and long are in decimal degrees TRX = -105.1621 #top right longitude TRY = 40.0868 #top right latitude BLX = -105.2898 #bottom left longitude BLY = 40.0010 #bottom left latitude

Run the program by typing:

python gpsmap.py

The program starts by getting some information from the user.

You will select to either run the program with a GPS device connected or you can load your own GPS NMEA sentences into a file called nmea.txt. Since you have your GPS connected, you will select your COM port and be presented with two mapping options: a position map…

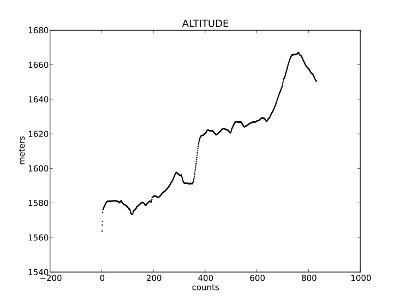

…or an altitude map.

Once you open the serial port to your GPS, the nmea.txt file will automatically be created and raw GPS NMEA data, specifically GPGGA sentences, will be logged in a private thread. When you make a map selection, the nmea.txt file is copied into a file called temp.txt, which is parsed for latitude and longitude (or altitude). The temp.txt file is created to parse the data so that we don’t corrupt or happen to change the main nmea.txt log file.

The maps are generated in their own windows with options to save, zoom, and hover your mouse over points to get fine grain x,y coordinates.

Also, the maps don’t refresh automatically, so as your GPS logs data, you will need to close the map window and run the map generation commands to get new data. If you close the entire Python program, the logging to nmea.txt halts.

This program isn’t finished by any means. I found myself constantly wanting to add features and fix bugs. I binged on Python for a weekend, simply because there are so many modules to work with: GUI tools, interfacing to the web, etc. It is seriously addicting. If you have any modifications or suggestions, please feel free to leave them in the comments below. Thanks for reading!

Getting Started with U-Center for u-blox

Introduction

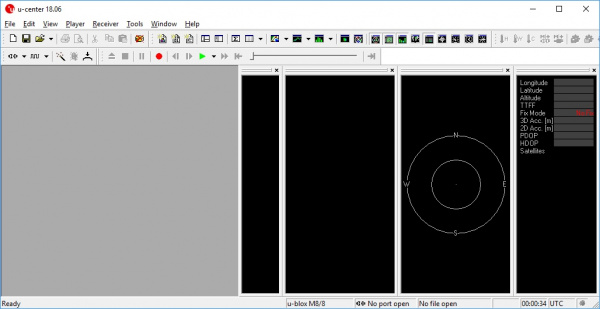

U-center from u-blox is a free software tool for configuring u-blox GPS receivers under Windows. U-center is a dense program with many interface elements. It can be overwhelming at first but over time it will become easier to use. For all its GUI weaknesses, it is very powerful for configuring the u-blox line of modules (such as the NEO-M8P-2 and SAM-M8Q to name a few). In this tutorial, we will be exploring some of its features with the NEO-M8P-2.

Required Software

The software can be obtained from u-blox. To follow along with this tutorial please download and install u-center. Once completed, open it.DOWNLOAD U-CENTER

Install Drivers

For this tutorial we’ll assume you have the SparkFun GPS-RTK but u-center can be used with any u-blox based product. Start by attaching a micro-B cable to the GPS-RTK board.

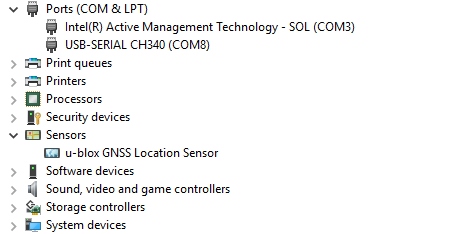

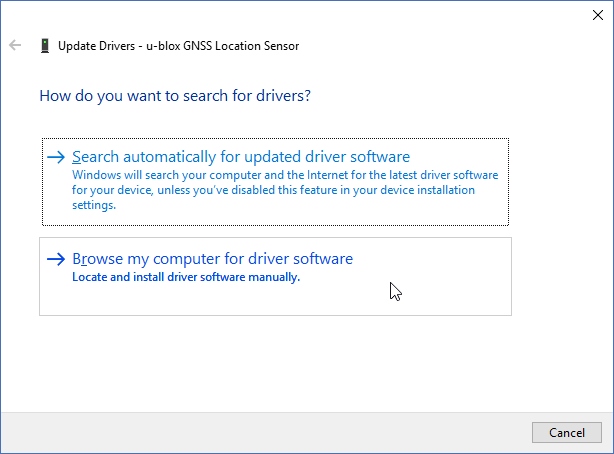

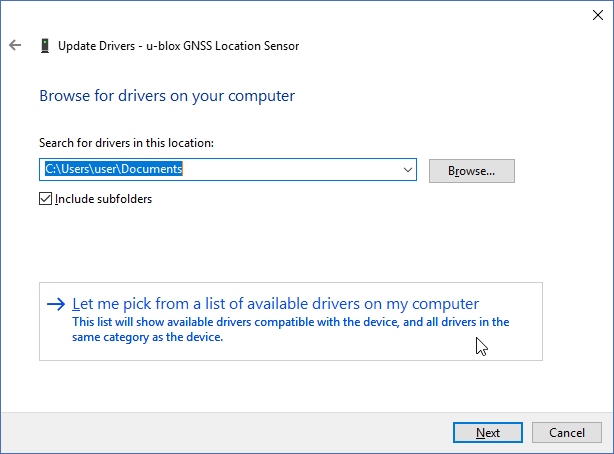

Now open Windows Device Manager. The NEO-M8 series has an annoying feature where the module comes up as a Windows Sensor rather than a serial device. If your u-blox receiver does not appear under COM ports then right click on the u-blox GNSS Location Sensor and then Update Driver. Next, click on Browse my computer for driver software.

Then “Let me pick”…

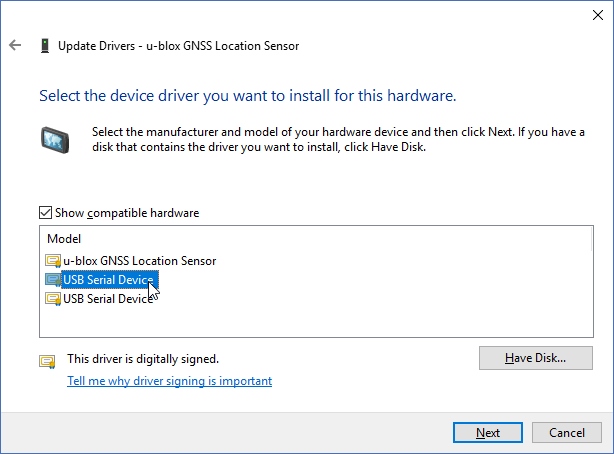

Select the first USB serial device.

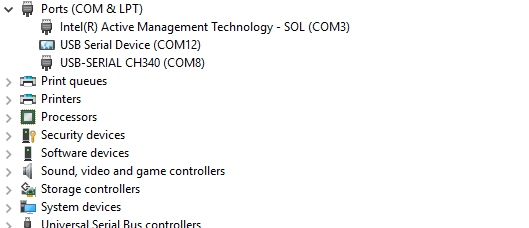

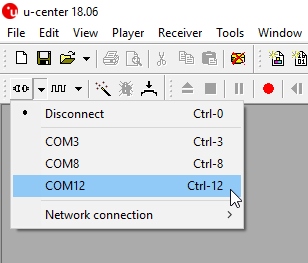

The SparkFun GPS-RTK board should now enumerate as a USB serial COM port. In the list below, the GPS-RTK board is COM12.

Return to u-center and drop down the port list. Select the COM port that is your RTK board. Congrats! You can now use u-center.

Configuring and Outputting NMEA Sentences

Let’s go over a few features you’ll likely use:

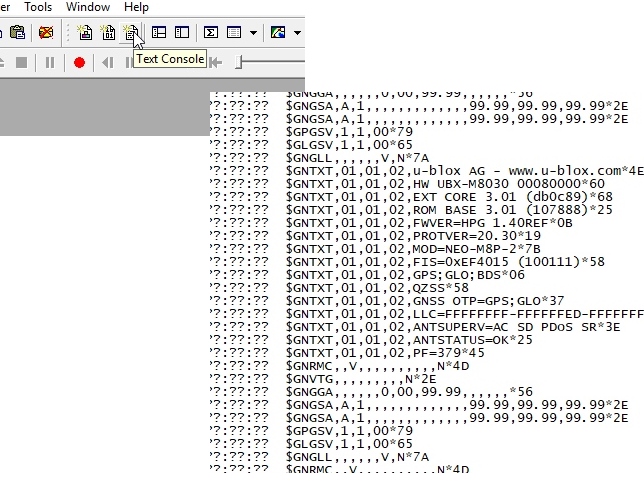

Text Console

The text console button will show you the raw NMEA sentences. This is handy for quickly inspecting the visible ASCII coming from the module over USB.

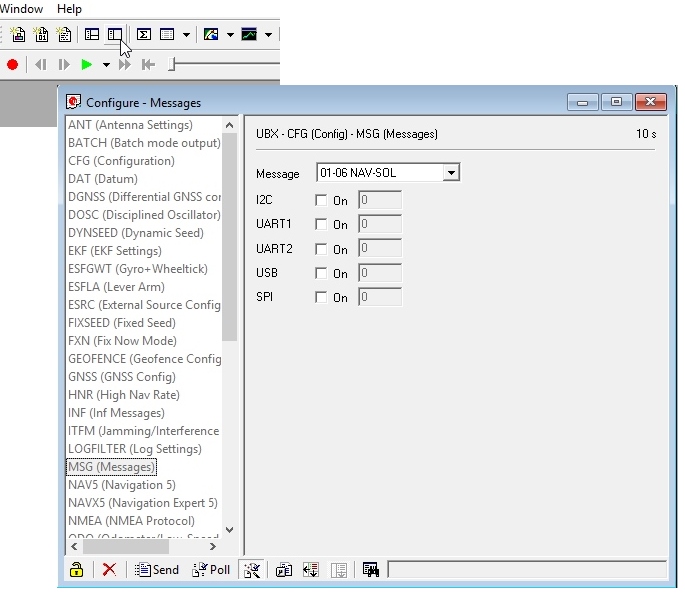

Configure

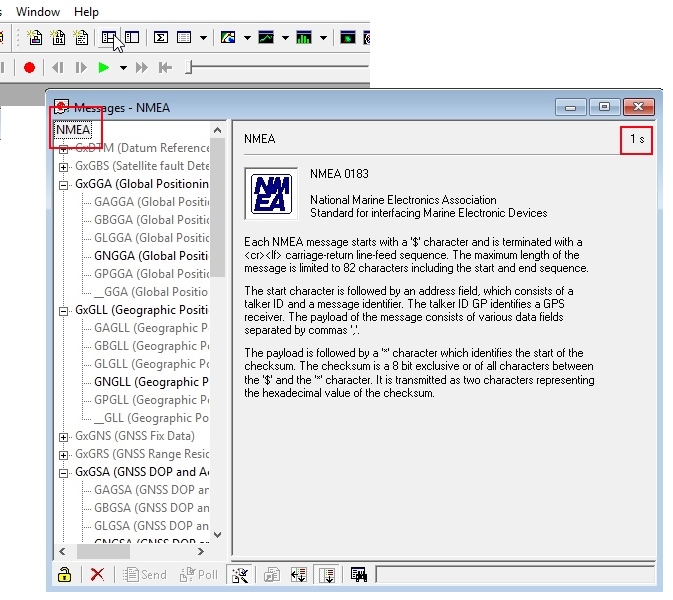

The configuration button opens the most powerful window. From this window you can inspect and configure new settings. It’s not obvious but when you click on a setting such as ‘MSG (Messages),’ u-center will poll the module for its current state. The ‘10s’ in the corner indicates how old the displayed information is. In this case it’s been 10 seconds since this setting was last queried. Click on the ‘Poll’ button to update the information. Go ahead and select the F0-00 NMEA GxGGA message. As you click the dropdown menu, the software will poll the current settings. It’s a bit disorienting at first but gets better over time.

The MSG configuration is very powerful. It allows you to enable or disable various NMEA sentences as well as binary protocols such as NAV-PVT (checkout the [full protocol datasheet](link text). Once a sentence is selected, such as GxGGA, the check boxes will be populated. If you want to disable the GxGGA sentence for the SPI interface, uncheck the SPI checkbox and then click ‘Send’. Congrats! The GxGGA sentence is no longer presented on the SPI interface. This raises an important fact:

Note: The NEO-M8 series has 4 interfaces: USB(serial), I2C, SPI, and UART. All interfaces can access information simultaneously. This means you can inspect configuration settings over the USB serial port while your Arduino makes setting changes over the I2C port. You can read NMEA sentences over the I2C port or send RTCM data into the module over SPI. It’s all highly configurable.

What is the USB Port on the NEO-M8P?

It’s like any other USB to serial device. It will enumerate on your computer as a COM port and acts as such. It is independent and separate from the UART port that is a dedicated TTL serial port.

If something is not accessible through u-center, it probably means that feature or setting is not compatible with the currently attached device. For example, the UART2 box is grayed out in the image above. The NEO-M8P does not have a second UART so you can’t address it.

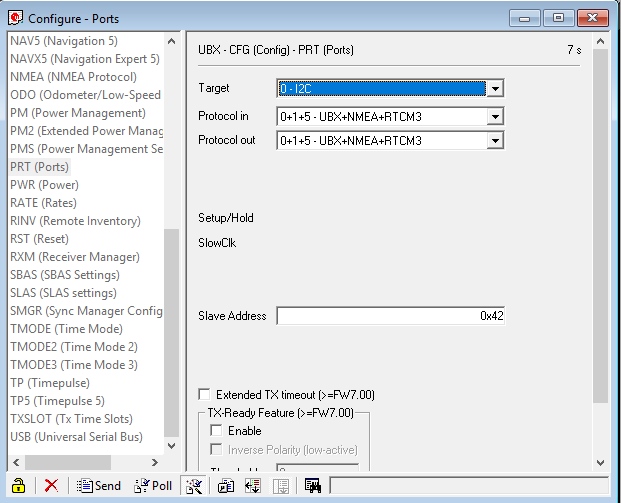

Ports

The Ports (PRT) sub-menu under Configuration is very helpful. You can do things like change the baud rate, I2C address, and protocols. Depending on your application, you may want to enable or disable entire interface protocols. For example, if you want to enable NMEA sentences for the SPI interface, you would do it here. Fortunately, the factory default for the NEO-M8P is good for I2C and UART1 for RTK purposes (input of RTCM3 is enabled for both ports).

This is also the menu that allows you to change the I2C address of your GPS-RTK. Because we are big fans of the Qwiic system, we’ll be using the GPS-RTK on the I2C bus. If we had another device on the bus that uses address 0x42 this menu will allow us to change the address of the GPS-RTK.

Poke around the various config menus. If you get your module into an unknown state you can unplug and replug to reset the settings.

Messages

The messages window will allow you to view the various sentences reported by the module. It’s not obvious but if you double click on ‘NMEA’, the tree of messages will fold away. Similarly, if you double click on ‘UBX’, it will expand showing the various UBX sentences. By default, many of these are not enabled.

Resources and Going Further

Ready to get hands-on with GPS?

We’ve got a page just for you! We’ll walk you through the basics of how GPS works, the hardware needed, and project tutorials to get you started.

Once you’ve mastered U-Center you’re ready to begin configuring your Ublox module! Check out some of these related tutorials:Building an Autonomous Vehicle: The BatmobileDocumenting a six-month project to race autonomous Power Wheels at the SparkFun Autonomous Vehicle Competition (AVC) in 2016.GPS-RTK Hookup GuideFind out where you are! Use this easy hook-up guide to get up and running with the SparkFun high precision GPS-RTK board.GPS-RTK2 Hookup GuideGet precision down to the diameter of a dime with the new ZED-F9P from Ublox.

Faktakoll på världen med data från Our World in Data

På Our World in Data hittar du data med tabeller och över 3000 diagram inom nästan 300 olika områden. Allt är open source och fritt att använda.

Ett perfekt ställe att gå till för att faktakolla hur saker och ting ser ut och förhåller sig i världen. Ypperlig källa för att källkritiskt granska påstående om t ex utsläpp, demografisk utveckling, politik, undervisning i olika länder m.m.

Det finns även specifika sidor för lärare mer anpassat och paketerat material som kan användas direkt i undervisningen.

SparkFun JetBot AI kit – monteringsinstruktioner

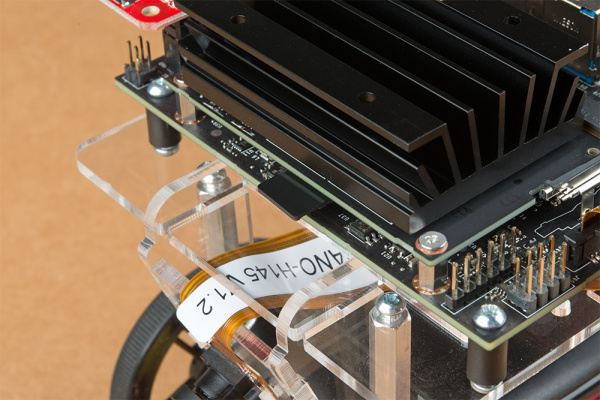

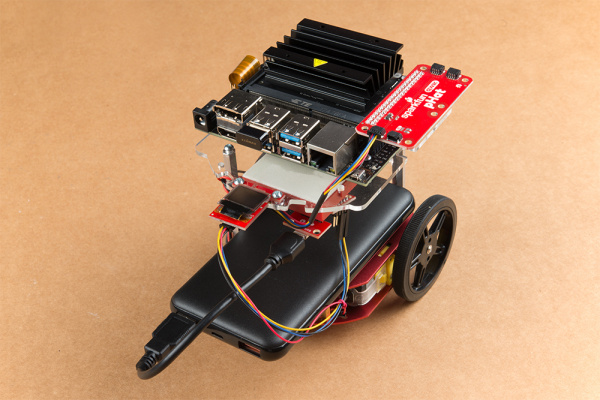

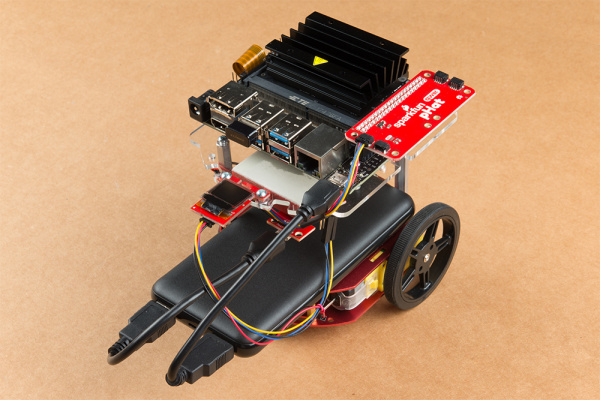

Assembly Guide for SparkFun JetBot AI Kit

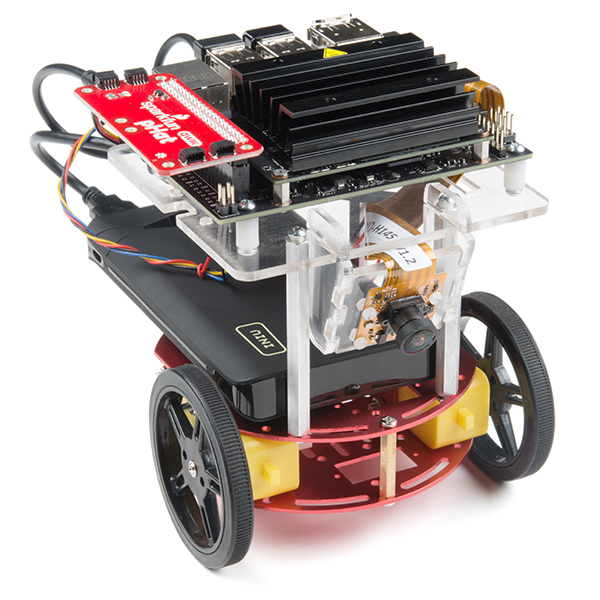

Introduction

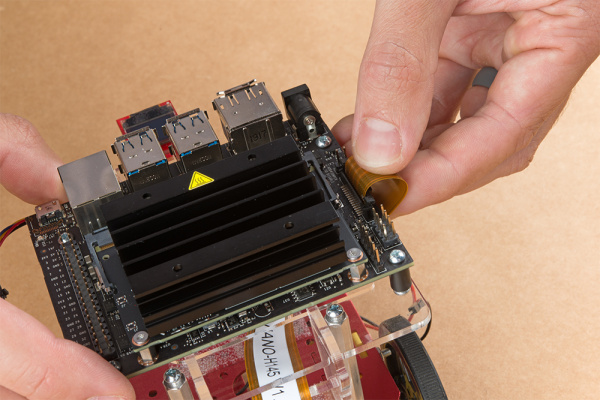

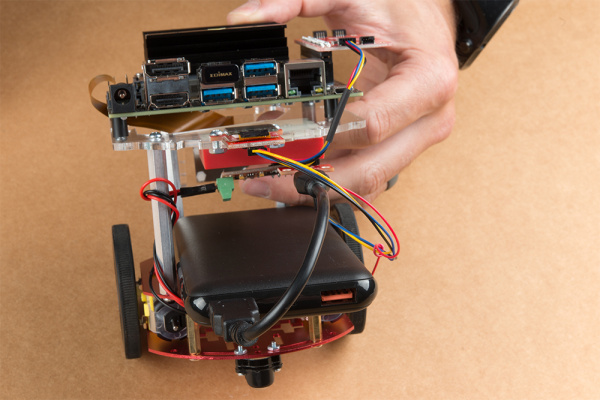

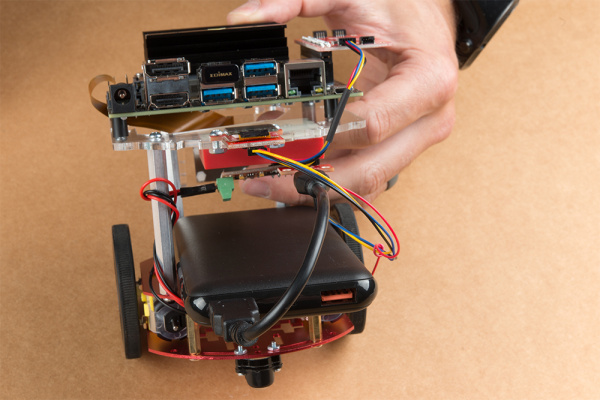

SparkFun’s version of the JetBot merges the industry leading machine learning capabilities of the NVIDIA Jetson Nano with the vast SparkFun ecosystem of sensors and accessories. Packaged as a ready to assemble robotics platform, the SparkFun JetBot Kit requires no additional components or 3D printing to get started – just assemble the robot, boot up the Jetson Nano, connect to WiFi and start using the JetBot immediately. This combination of advanced technologies in a ready-to-assemble package makes the SparkFun JetBot Kit a standout, delivering one of the strongest robotics platforms on the market. This guide serves as hardware assembly instructions for the two kits that SparkFun sells; Jetbot including Jetson Nano & the Jetbot add-on kit without the NVIDIA Jetson Nano. The SparkFun JetBot comes with a pre-flashed micro SD card image that includes the Nvidia JetBot base image with additional installations of the SparkFun Qwiic Python library, Edimax WiFi driver, Amazon Greengrass, and the JetBot ROS. Users only need to plug in the SD card and set up the WiFi connection to get started.

Note: We recommend that you read all of the directions first, before building your Jetbot. However, we empathize if you are just here for the pictures & a general feel for the SparkFun Jetbot. We are also those people who on occasion void warranties & recycle unopened instructions manuals. However, SparkFun can only provide support for the instructions laid out in the following pages.

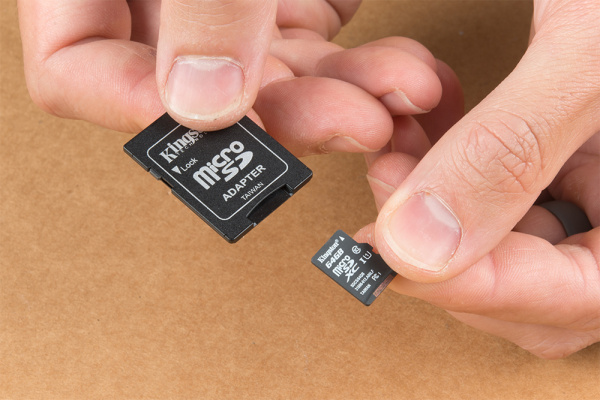

Attention: The SD card in this kit comes pre-flashed to work with our hardware and has the all the modules installed (including the sample machine learning models needed for the collision avoidance and object following examples). The only software procedures needed to get your Jetbot running are steps 2-4 from the Nvidia instructions (i.e. setup the WiFi connection and then connect to the Jetbot using a browser). Please DO NOT format or flash a new image on the SD card; otherwise, you will need to flash our image back onto the card.

If you accidentally make this mistake, don’t worry. You can find instructions for re-flashing our image back onto the SD card in the software section of the guide

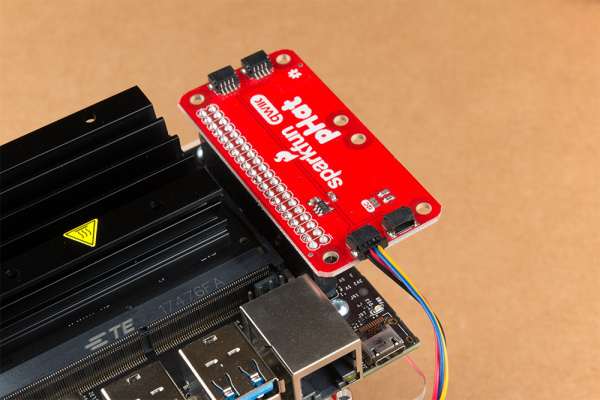

The Jetson Nano Developer Kit offers extensibility through an industry standard GPIO header and associated programming capabilities like the Jetson GPIO Python library. Building off this capability, the SparkFun kit includes the SparkFun Qwiic pHat for Raspberry Pi, enabling immediate access to the extensive SparkFun Qwiic ecosystem from within the Jetson Nano environment, which makes it easy to integrate more than 30 sensors (no soldering and daisy-chainable).

The SparkFun Qwiic Connect System is an ecosystem of I2C sensors, actuators, shields and cables that make prototyping faster and less prone to error. All Qwiic-enabled boards use a common 1mm pitch, 4-pin JST connector. This reduces the amount of required PCB space, and polarized connections mean you can’t hook it up wrong.

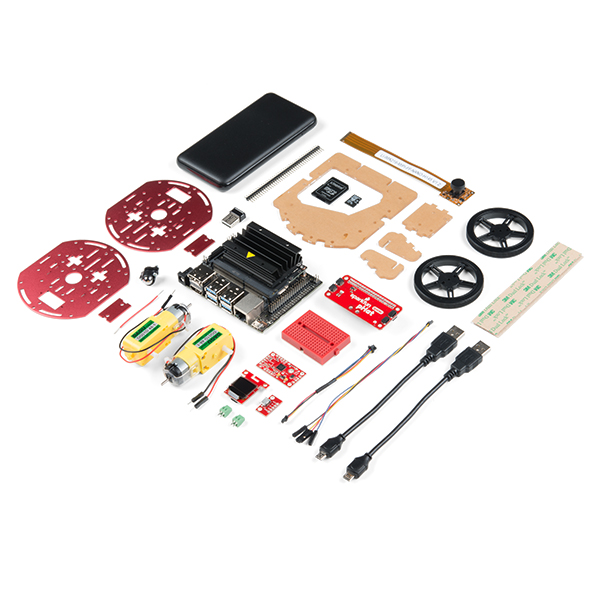

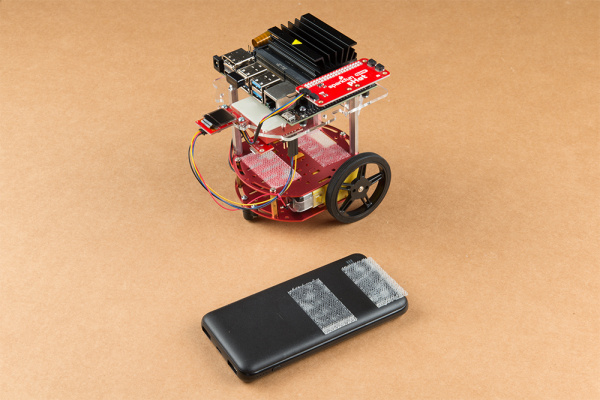

Materials

The SparkFun Jetbot Kit contains the following pieces; roughly top to bottom, left to right.

| Part | Qty |

|---|---|

| Circular Robotics Chassis Kit (Two-Layer) | 1 |

| Lithium Ion Battery Pack – 10Ah (3A/1A USB Ports) | 1 |

| Ball Caster Metal – 3/8″ | 1 |

| Edimax 2-in-1 WiFi and Bluetooth 4.0 Adapter | 1 |

| Header – male – PTH – 40 pin – straight | 1 |

| 2 in – 22 gauge solid core hookup wire (red) | 1 |

| Shadow Chassis Motor (pair) | 1 |

| Jetson Dev Kit (Optional) | 1 |

| SparkFun JetBot Acrylic Mounting Plate | 1 |

| SparkFun Jetbot image (Pre Flashed) | 1 |

| Leopard Imaging 145 FOV Camera | 1 |

| Screw Terminals 2.54mm Pitch (2-Pin) | 2 |

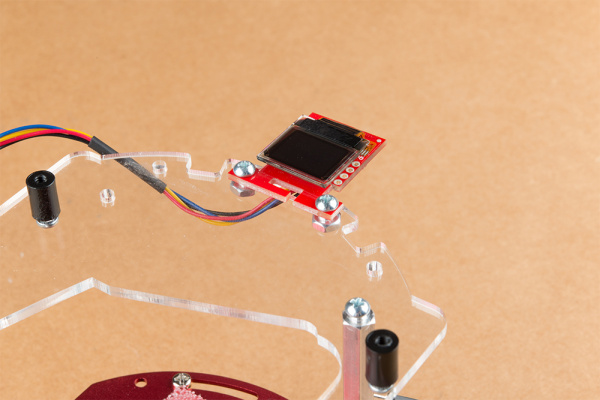

| SparkFun Micro OLED Breakout (Qwiic) | 1 |

| SparkFun microB USB Breakout | 1 |

| SparkFun Serial Controlled Motor Driver | 1 |

| Breadboard Mini Self-Adhesive Red | 1 |

| SparkFun Qwiic HAT for Raspberry Pi | 1 |

| SparkFun JetBot Acrylic sidewall for camera mount | 2 |

| SparkFun JetBot Acrylic Camera mount & 4x nylon mounting hardware | 1 |

| Qwiic Cable – 100mm | 1 |

| Qwiic Cable – Female Jumper (4-pin) | 1 |

| Wheels & Tires – included as part of circular robotics chassis | 2 |

| USB Micro-B Cable – 6″ | 2 |

| Dual Lock Velcro | 1 |

The SparkFun Jetbot Kit contains the following hardware; roughly top to bottom, left to right.

| Part | Qty |

|---|---|

| Hex Standoff #4-40 Alum 2-3/8″ | 3 |

| Standoff – Nylon (4-40; 3/8in.) | 10 |

| 1/4″ Phillips Screw with 4-40 Thread | 20 |

| Machine Screw Nut – 4-40 | 10 |

| Circular Robotics Chassis Kit (Two-Layer) Hardware | 1 |

Recommended Tools

We did not include any tools in this kit because if you are like us you are looking for an excuse to use the tools you have more than needing new tools to work on your projects. That said, the following tools will be required to assemble your SparkFun Jetbot.

- Small phillips & small flat head head screwdriver will be needed for chassis assembly & to tighten the screw terminal connections for each motor. We reccomend the Pocket Screwdriver Set; TOL-12268.

- Pair of scissors will be needed to cut the adhesive Dual Lock Velcro strap to desired size; recommended, but not essential..

- Soldering kit for assembly & configuration of the SparkFun Serial Controlled Motor Driver – example TOL-14681

- Optional– adjustable wrench or pliers to hold small components (nuts & standoffs) in place while tightening screws; your finger grip is usually enough to hold these in place while tightening screws & helps to ensure nothing is over tightened.A Note About Directions

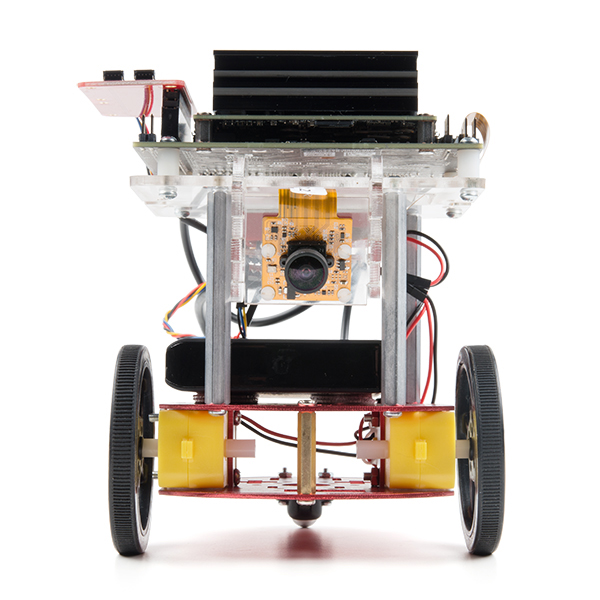

When we talk about the ”front,” or ”forward” of the JetBot, we are referring to direction the camera is pointed when the Jetbot is fully assembled. ”Left” and ”Right” will be from the perspective of the SparkFun Jetbot.

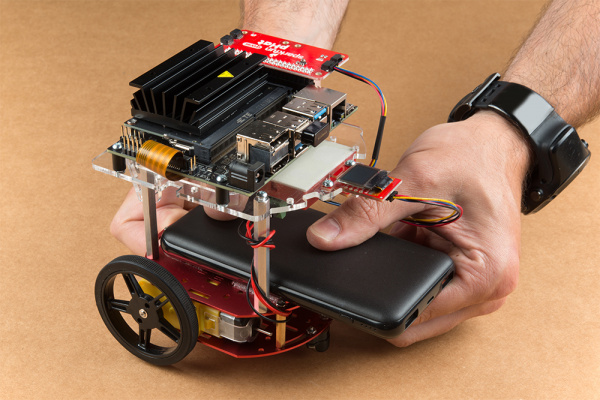

1. Circular Robotics Chassis Kit (Two-Layer) Assembly

If you prefer to follow along with a video, check out this feature from the chassis product page. You do not need to use the included ball caster as a larger option has been provided for smoother operation.

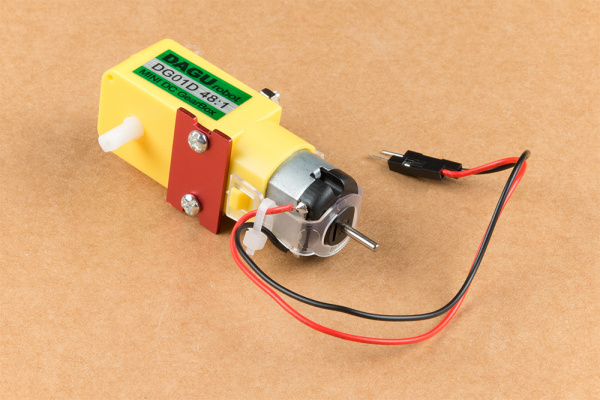

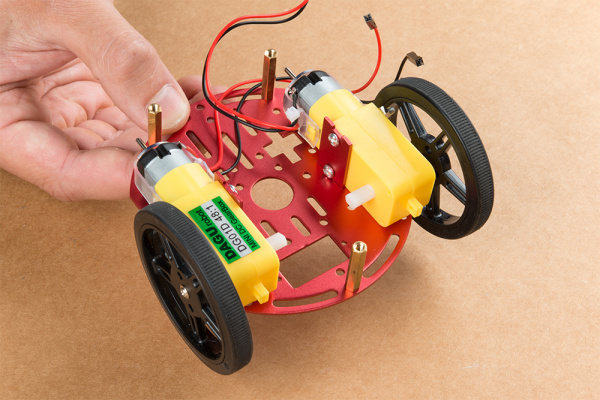

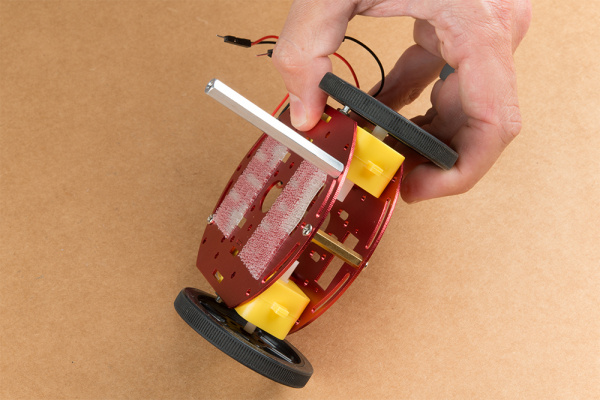

Start by attaching the chassis motor mount tabs to each of the ”Shadow Chassis Motors (pair)” using the long threaded machine screws & nuts included with the Circular Robotics Chassis Kit.

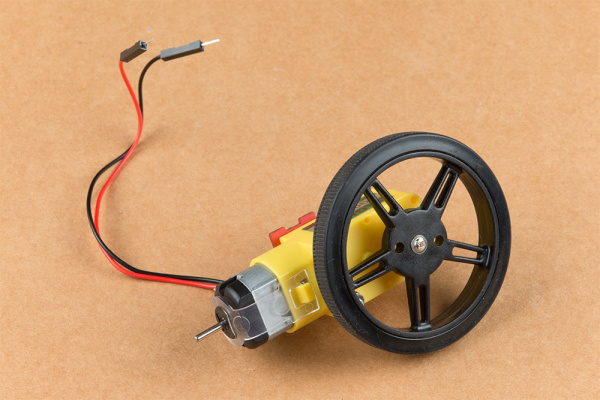

Fit the rubber wheels onto the hubs, install the wheel onto each motor, & fix them into position using the self tapping screws included with the Circular Robotics Chassis Kit.

Install the brass colored standoffs included with the Circular Robotics Chassis Kit; two in the rear and one in the front. The rear of the SparkFun Jetbot will be on the side of the plate with the two ”+” sign cut outs. The rear of the motor will be opposite the wheel where the spindle extends. This orientation ensures the widest base & most stable set up for your Jetbot.

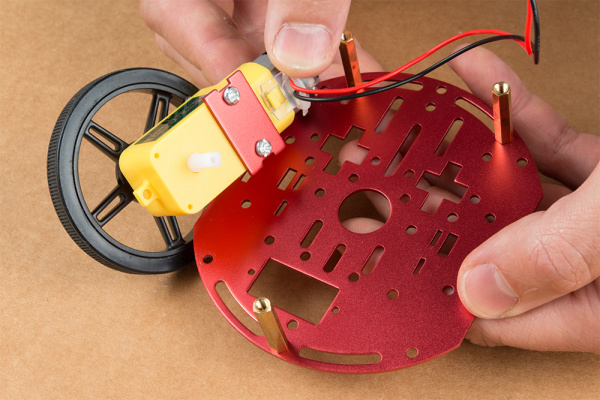

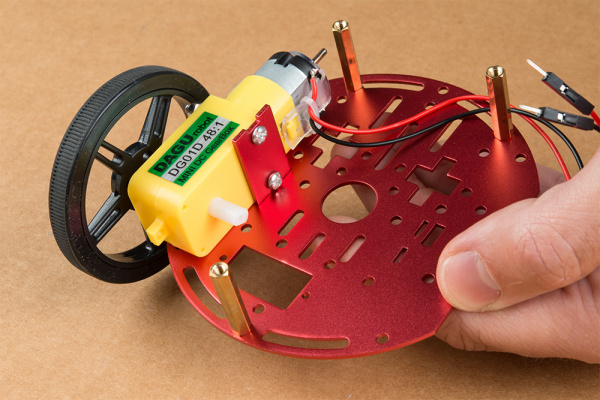

The motor mounts fit into two mirrored inlets in each base plate as shown. Install the motors opposite of one another.

Depending on how you install the motor mounts to each motor will dictate how the motor can be installed on the base plate. Note: Do not worry about the motor orientation as you will determine proper motor operation in how you connect the motor leads to the SparkFun Serial Controlled Motor Driver. Notice how in the picture below one motor has the label facing up, while the other has the label facing down.

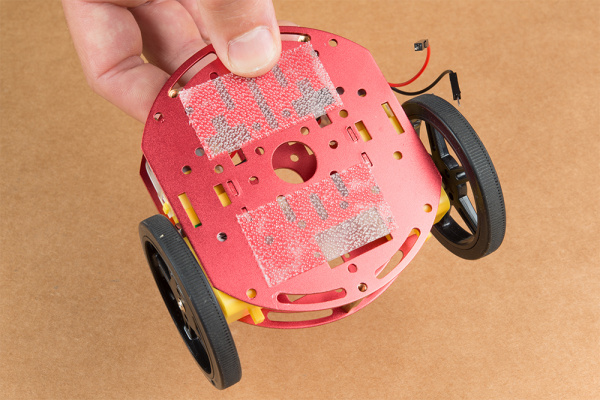

Place the other circular robot chassis plate on top of and align the two ”+” and the motor mount tab recesses. Hold the sandwiched chassis together with one hand and install the remaining Phillips head screws included with the Circular Robotics Chassis Kit through the top plate & into the threaded standoffs.

Your main chassis is now assembled! The Circular Robotics Chassis Kit also contains a very small caster wheel assembly, but we have included a larger metal caster ball to increase the stability of the SparkFun Jetbot. We will cover the installation of this caster ball later in the tutorial.

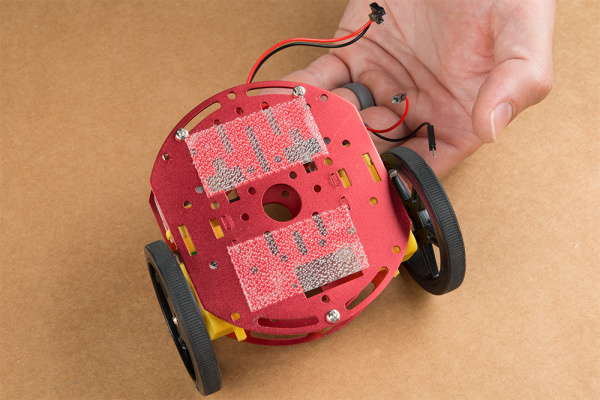

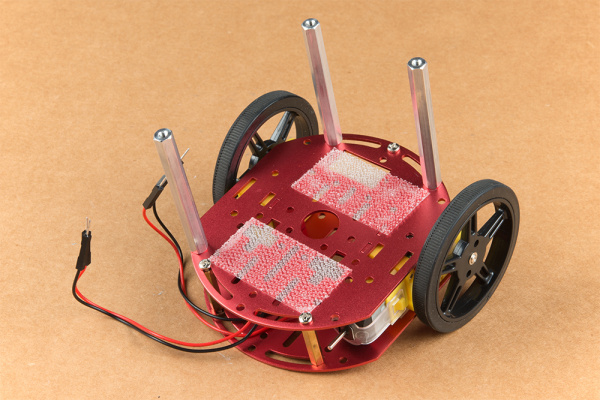

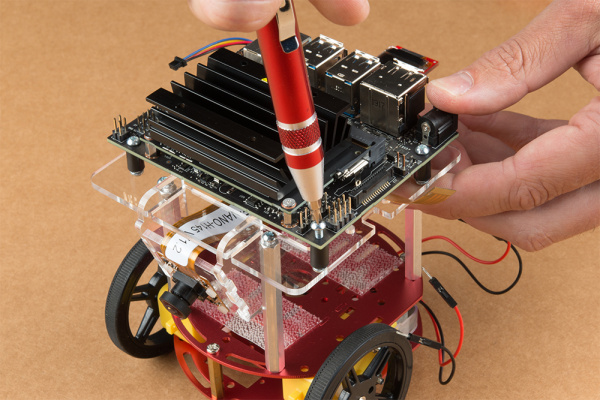

Utilize three of the included 1/4 in 4-40 Phillips Screws through the top chassis plate with threads facing up & install the 2-3/8 in #4-40 Aluminum Hex Standoff until they are finger tight.

The aluminum stand offs should be pointing up as shown below.

The SparkFun JetBot acrylic mounting plate is designed to have two of these aluminum standoffs in the front & one in the rear. We recommend the rear standoff on the left side of the chassis (as shown) so the 6 in microB usb cables that will be installed later can more easily span the gap needed to power the JetBot.

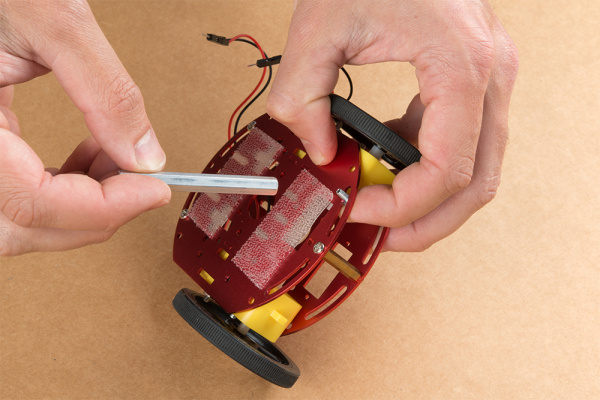

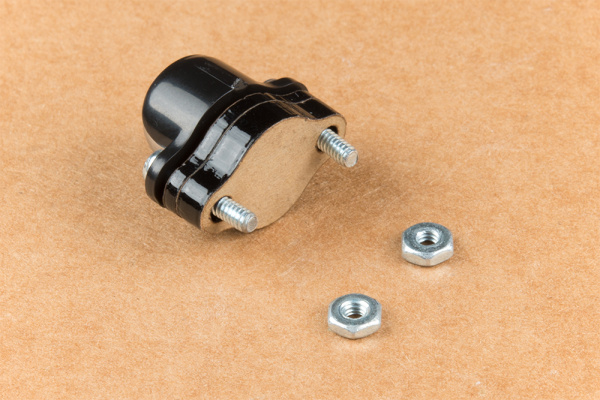

Un-package the 3/8 in Metal Caster Ball and thread the mounting screws through all pieces as shown. Note the full stack height will help balance the Jetbot in a stable position.

Install the caster wheel using the Phillips head screws and nuts included with the 3/8 in caster ball assembly. The holes on the caster assembly are spaced to fit snug on the innermost segment of the angular slots near the rear of the lower plate on the JetBot chassis. Again, hand tight is just fine. Note: if you over tighten these screws it will prevent the ball from easily rotating in the plastic assembly. However, too loose and it may un-thread; go for what feels right

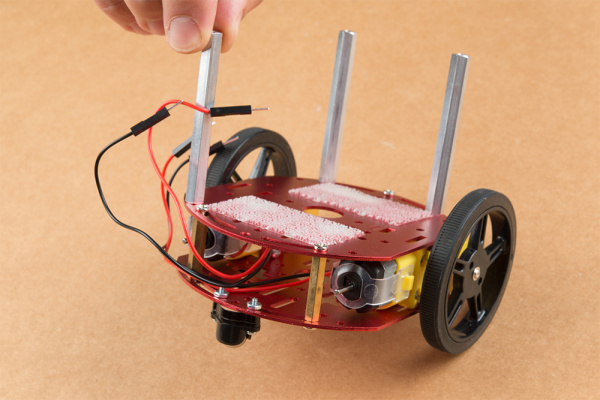

After you have installed the caster & aluminum standoffs, thread the motor wires through the back of the chassis standoffs for use later.

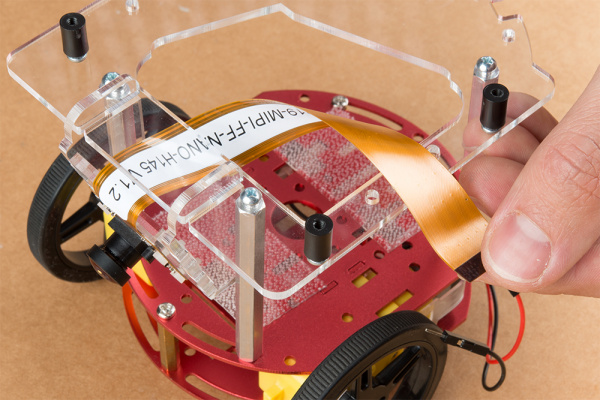

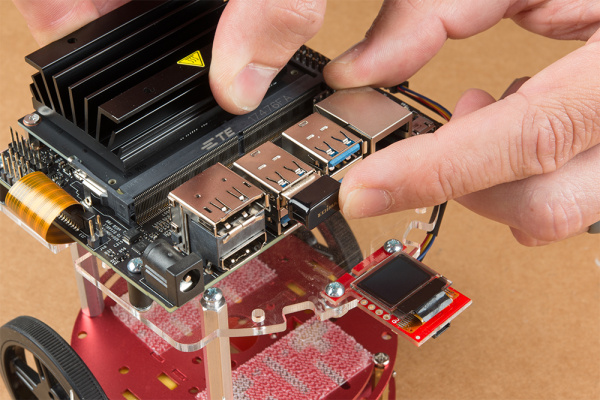

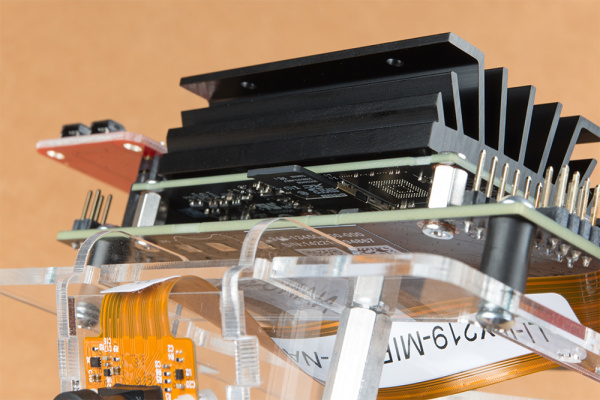

2. Camera Assembly & Installation

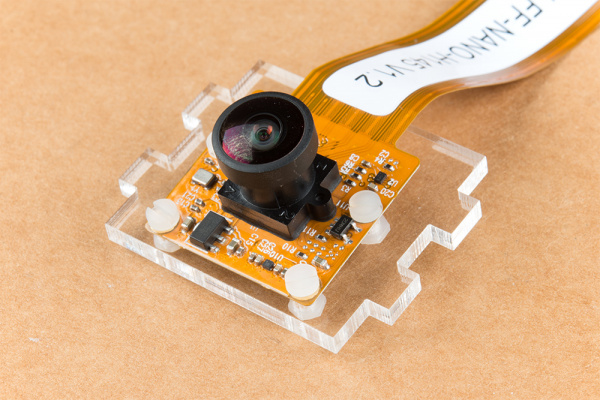

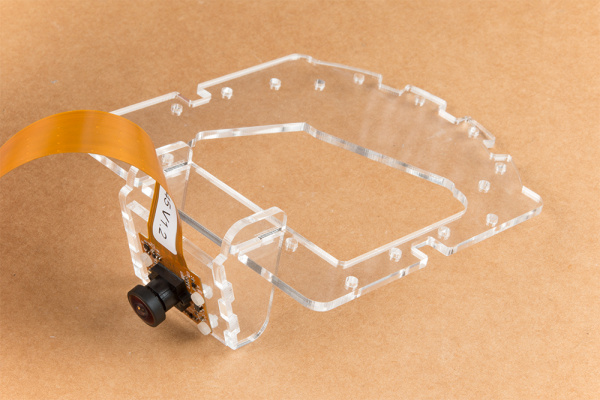

Unpackage the Leopard Imaging camera & align the four holes in the acrylic mounting plate with those on the camera.

Note: ensure that the ribbon cable is extending over the acrylic plate on the edge that does not have mounting holes near the edge; as shown below.

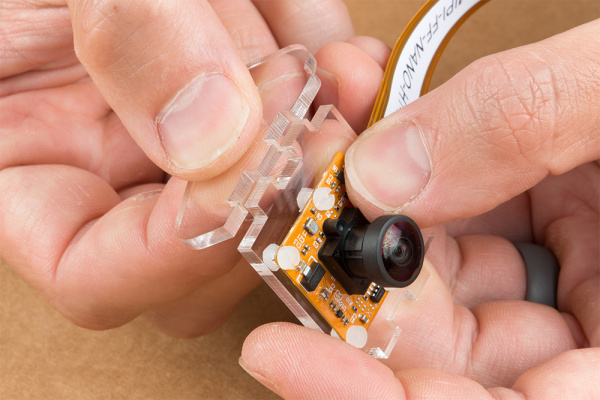

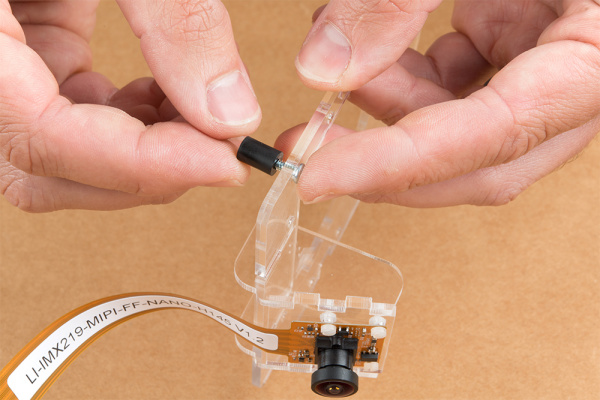

Place all four nylon flathead screws through the camera & acrylic mounting plate prior to fully tightening the nylon nuts. This will ensure equal alignment across all four screws. Tighten the screws while holding the nuts with finger pressure in a rotating criss cross pattern; similar to how you tighten lug nuts on a car rim.

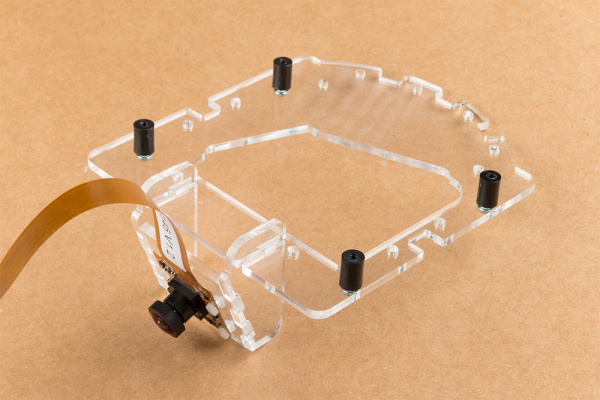

Align one acrylic sidewall with the camera mounting plate as shown below ensuring that the widest section of the sidewall is oriented to the top of the camera mount where the ribbon cable extends.

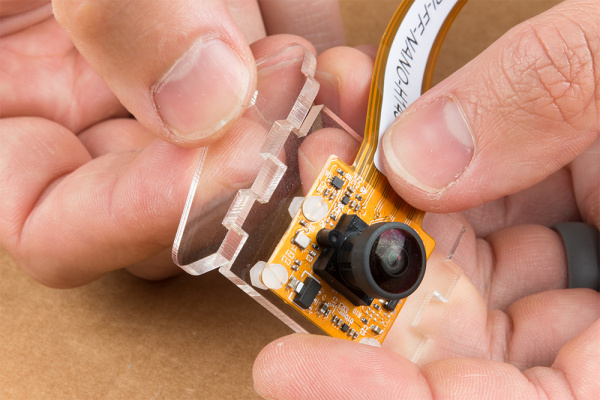

Apply even pressure on each piece until they fit together. Note: these pieces are designed to have an interference fit and will have a nice, satisfying ”click” when they fit together.

Repeat this process on the other side to fully assemble the camera mount.

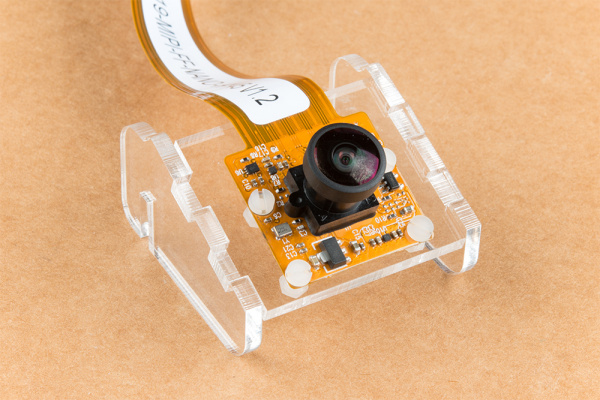

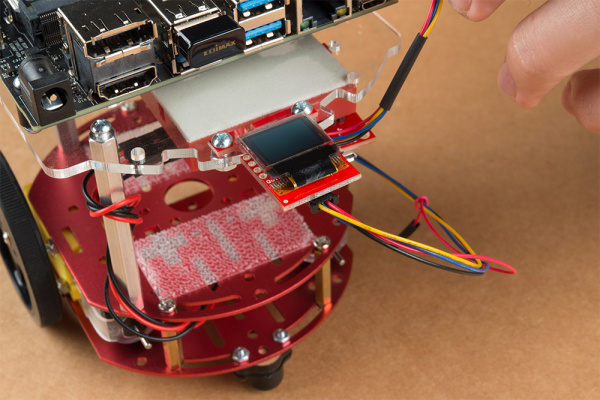

The camera mount should now be installed to the SparkFun Jetbot acrylic mounting plate using the overlapping groove joints. Ensure that the cut out on the acrylic mounting plate is facing towards the front/right of the Jetbot as shown. This will ensure that there is plenty of room for the camera ribbon cable to pass around the assembly and up to the Jetson nano camera connector.

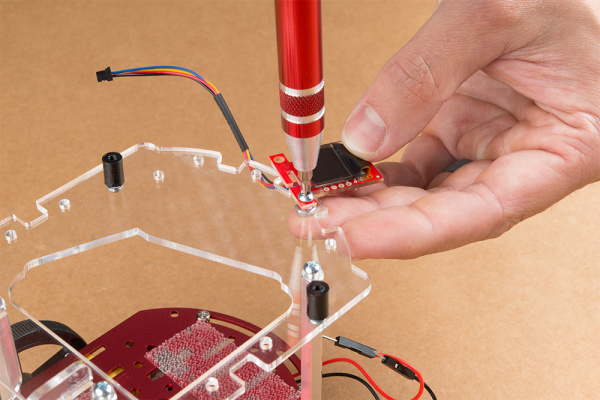

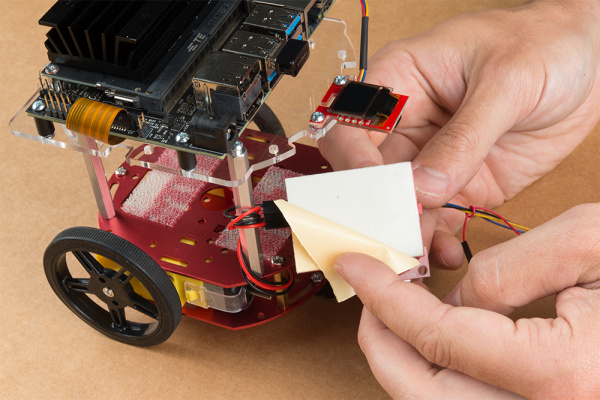

Install four of the nylon standoffs to the top of the SparkFun Jetbot acrylic mounting plate using four of the included 1/4 in 4-40 Phillips head screws as shown below.

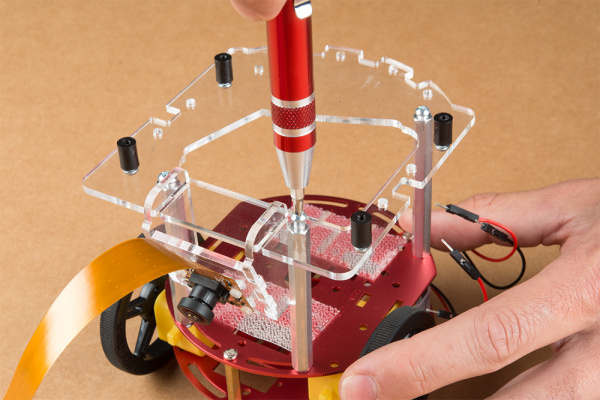

Utilize three more of the 1/4 in 4-40 Phillips head screws to install the SparkFun Jetbot acrylic mounting plate to the aluminum standoffs extending from the Two-layer circular robotics chassis as shown below.

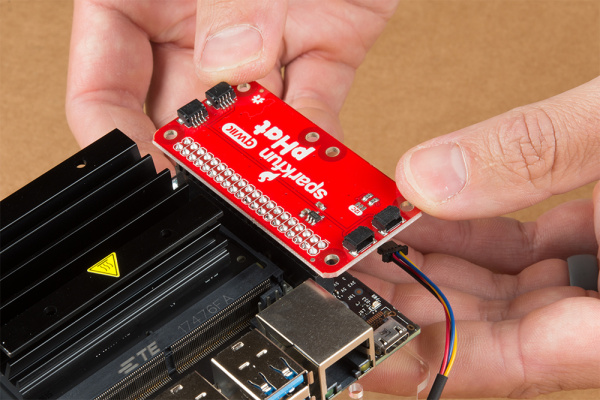

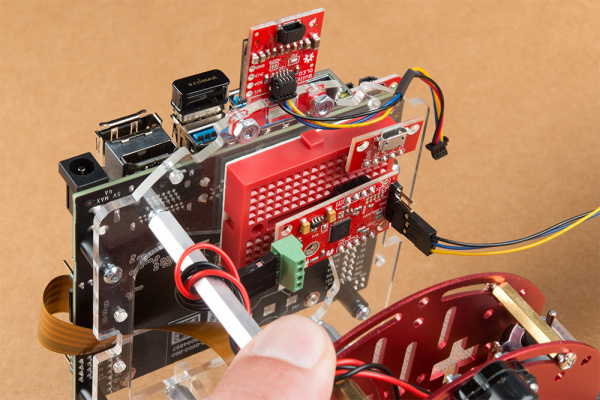

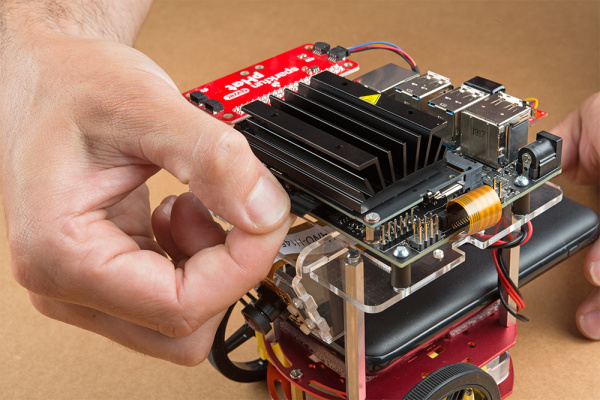

3. Motor Driver Assembly & Configuration

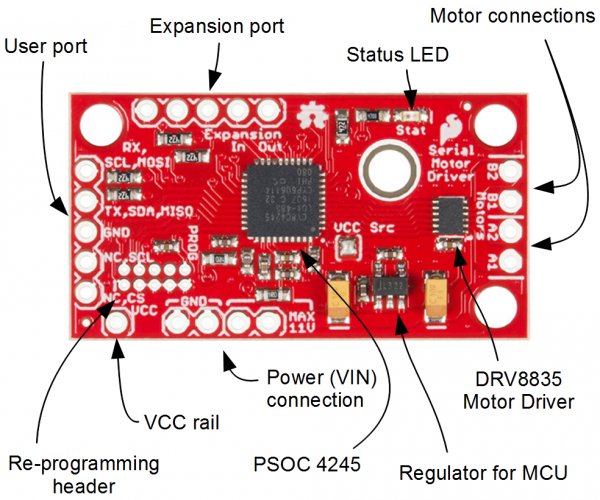

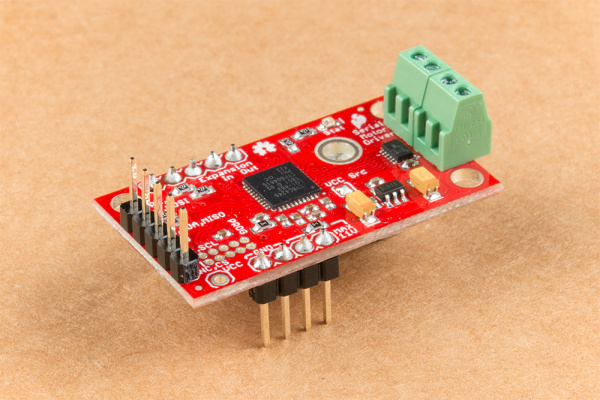

To get started, make sure that you are familiar with the SparkFun Serial Controlled Motor Driver Hookup Guide.

We also recommend a detailed review of the Hardware Overview of the SparkFun Serial Controlled Motor Driver Here.

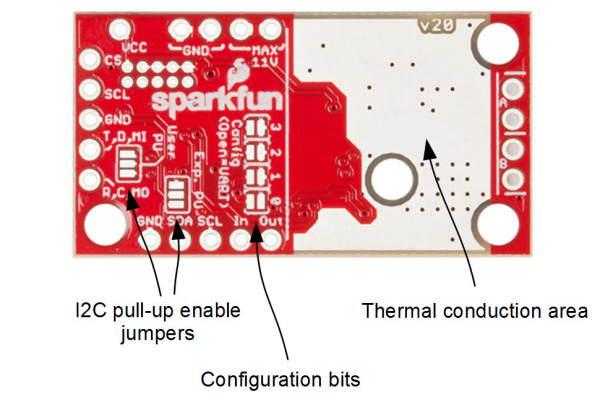

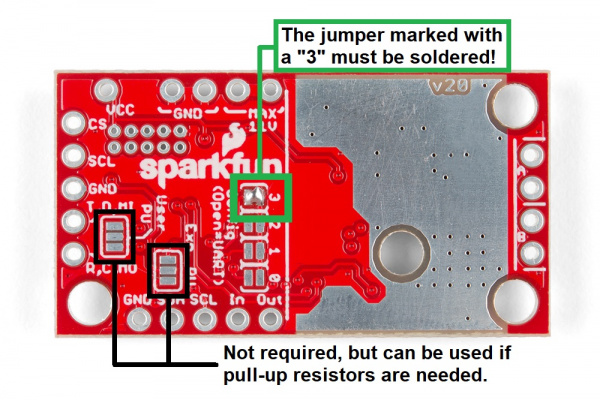

You will need to solder both triple jumpers labeled below as ”I2C pull-up enable jumpers” as the SparkFun pHat utilizes the I2C protocol. The default I2C address that is used by the pre-flashed SparkFun Jetbot image is 0x5D which is equavalent to soldering pad #3 noted as ”configuration bits” on the back of the SparkFun serial controlled motor driver; see below. You will need to create a solder jumper on pad #3 only for the SparkFun Jetbot Image to work properly.

Layout of jumpers on the Serial Controlled Motor Driver.

Jumper 3 of theConfiguration Bitsproperly soldered.

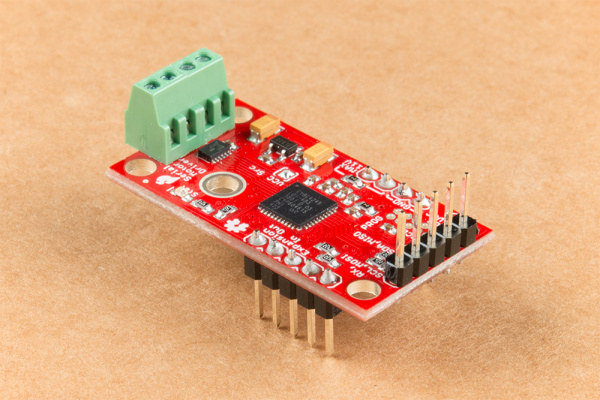

Your completed Serial Controlled motor drive should look somewhat similar to the board shown below.

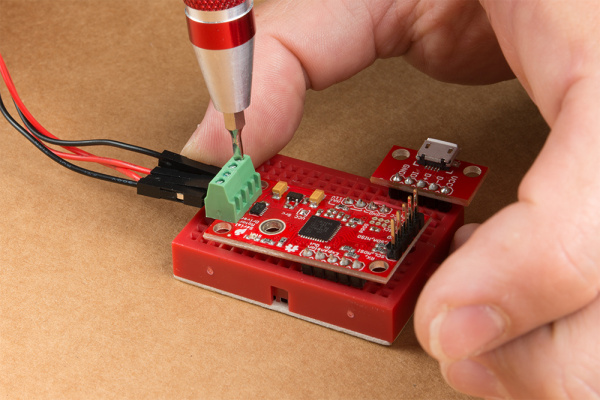

- The 2-pin screw terminals are soldered to the ”Motor Connections.”

- Break off 4 Male PTH straight headers and solder into the ”Power (VIN) connection” points.

- Break off 5 Male PTH straight headers and solder into the ”Expansion port” points. These will not be used, but will provide additional board stability when installed into the mini breadboard.

- Break off 5 Male PTH straight headers and solder into the ”User port” points for connection into the included Female Jumper Qwiic cables.

Break off 5 Male PTH straight headers and solder into the breakout points on the SparkFun microB USB Breakout.

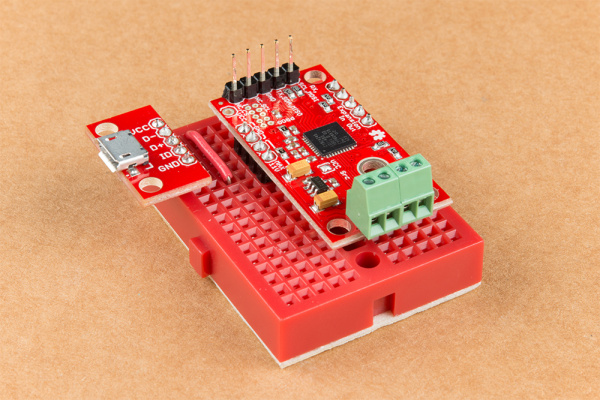

Install both the SparkFun Serial Controlled Motor Driver & the SparkFun microB Breakout board on the included mini breadboard so the ”GRD” terminals for each unit share a bridge on one side of the breadboard.

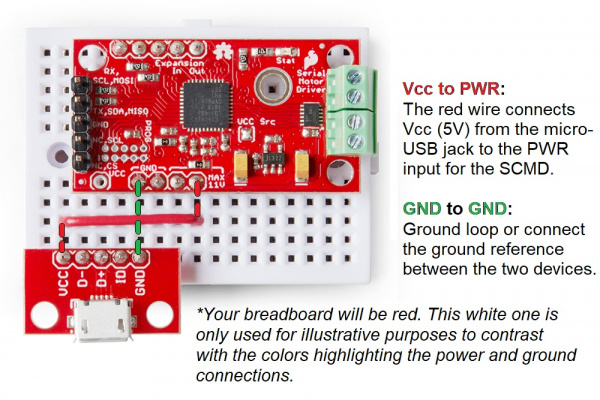

Utilize the included 2 in – 22 gauge solid core hookup wire (red) to bridge the ”VCC” pin for the SparkFun microB Breakout to either (VIN) connection point on the SparkFun Serial Controlled Motor Driver as shown below.

Required power connections between the micro-USB breakout and the Serial Controlled Motor Driver.

Competed assembly of the micro-USB breakout and Serial Controlled Motor Driver on the breadboard.

Utilize a small flat head screwdriver to loosen the four connection points on the screw terminals. When inserting the motor connection wires, note the desired output given the caution noted in section #1 of this assembly guide.